Sales Compensation and Recommendations as the Fund of the Month†

Abstract

This study analyzes whether mutual fund distributors are more likely to recommend products with higher sales compensation to maximize their profit. The lists of the ‘fund of the month’ on their webpages are utilized from April of 2015 to August of 2015. A simple comparative analysis shows that the average sales fees and the average front-end load are significantly higher in the recommended funds among the A share class of domestic equity funds. The results of a regression analysis confirm that funds with high sales compensation levels are more likely to be recommended. This holds true for both domestic equity funds and hybrid bond funds even after controlling for fund age, fund size, and past returns.

Keywords

Mutual Fund, Sales Compensation, Conflict of Interest

JEL Code

G20, G24, G28

I. Introduction

Since the global financial crisis, the importance of financial consumer protection has been strengthened. The UK and Australia have especially focused on conflicts of interest in recommendation services caused by the compensation scheme employed. From 2013, they banned commissions for financial advisors who recommend retail investment products to consumers. However, in Korea, sales personnel who recommend retail investment products in financial institutions may still prioritize products with higher commissions than the best products for the consumers.

Recently, the financial authorities in South Korea introduced the IFA (independent financial advisor) to ease conflicts of interest in existing sales channels. However, Korean consumers do not recognize possible conflicts of interest, which can easily stem from the sales compensation scheme, and the demand for IFAs is very low in the market.1 Therefore, to activate the demand for IFAs, it is necessary to make consumers aware of the possibility of the conflicts of interest in the product recommendation of fund distributors.

This study analyzes the relationship between product recommendations by mutual fund companies and their corresponding sales compensation amounts. Specifically, the recommendation lists posted on the webpage as the fund of the month are analyzed. This approach serves to confirm whether financial institutions attempt to sell products with higher remuneration.

Mutual fund investors must pay various expenses to the sales personnel for the services of investment soliciting, product recommendations and the conclusion of a contract. Among mutual funds, fee structures and sizes vary.2 Hence, mutual fund distributors have an incentive to recommend a fund product with a greater sales fee or commission to maximize their profit. Therefore, this study focuses on conflicts of interest which can arise due to this type of sales compensation. Therefore, this study analyzes the effects of seller incentives on recommending what is termed the fund of the month. The roles of brokerage firms or asset management companies are not the main concern of this study.3

Some studies analyzed domestic equity funds before 2010 to examine conflicts of interest. Shin and Cho (2014) show that the mutual funds with the higher sales fees show higher fund inflows. Won (2009), Cho and Shin (2012) and Ban (2015) show a negative or insignificant relationship between ongoing sales fees and rates of return.

These studies confirm that policies are needed to ease conflicts of interest in the fund market. Accordingly, the compensation system of funds has changed significantly since 2010 in Korea. The structure of fees has diversified into various share class funds. The sales fee amounts have also fallen. However, these changes have made it difficult to analyze the effects of sales compensation on inflows in the market recently. Information about fund inflow and outflow amounts are not divided into share class levels. Thus, though an analysis remains necessary, related studies are limited.

In this context, the present study utilizes lists of the ‘fund of the month’ posted on financial institutions’ web pages from April of 2015 to August of 2015. In particular, the sales compensation amounts, in this case ongoing sales fees and one-time front-end load fees, are compared between the funds on the lists versus those which are not recommended. A regression analysis is also conducted, and these results show that funds with high sales compensation amounts are more likely to be recommended even after controlling for other characteristics of the mutual funds.4

This paper is organized as follows. Section II introduces related studies, and Section III covers the background of the fund market in Korea and the research question. Section IV presents the comparative analysis, and Section V presents the regression results. Section VI concludes the paper.

II. Literature Review

The issue of conflict of interest in the retail investment products is related to the problem of principal-agent when the incentive scheme is inconsistent (Arrow, 1963; Hormstrom, 1982). This study focuses on conflicts of interest that arise during the product recommendation process. This problem is caused by the fact that sales personnel receive compensation from the product manufacturer indirectly instead of receiving an advisory fee from the consumers directly.

The literature indicates that recommendation services in financial markets are distorted due to indirect commissions. According to Mullainathan et al. (2012), financial advisors tend to recommend a portfolio with transaction and management costs higher than those of index funds. Anagol et al. (2017) find that in India, life insurance sellers recommend products with higher commissions for themselves despite the fact that other products are better for consumers.

Previous studies analyze conflicts of interest in the financial market, reporting higher sales amounts for products with higher commissions. Siri and Tufano (1998) and Christoffersen et al. (2013) report a positive relationship between the inflow of U.S. mutual funds and commission sizes.

The Korean literature also focuses on the equity mutual fund market. Before 2010, share class C funds, which receive high ongoing sales fees, dominated the Korean mutual fund market. However, they were cited as having excessive sales fees, and the sellers did not provide maintenance services in exchange for the ongoing sales fees. In this context, Shin and Cho (2014) report a positive relationship between sales fees and fund inflows, suggesting a conflict of interest. Shin and Cho (2014) analyze C-Class domestic equity fund from 2007 to 2010, finding a significant positive relationship in a sample of funds with no affiliated asset management company. In contrast, among funds with affiliated asset management companies, the relationship is negative or insignificant.

Other strands of studies analyze the relationship between sales compensation and fund performance in the domestic equity fund market. Won (2009) pointed out that funds with higher sales fees show lower rates of return, and the amounts of the sales fees are high for funds sold by banks. Cho and Shin (2012) also report a negative relationship between sales fee amounts and fund performance. Ban (2015) analyzes equity funds between 2001 and 2009, reporting no significant relationship between risk-adjusted returns and sales fee amounts.

Despite the fact that earlier studies showed evidence of a conflict of interest in the mutual fund market in Korea, there is a lack of more recent research on conflicts of interest in the mutual fund market. After 2010, the scheme of sales compensation became more diversified. There are now sales fees which decrease over time (C1, C2) and those for funds sold online (E class). Although various share class funds have been introduced as mutual funds, information about outflow and inflow amounts is not distinguished at the share class level.5

For this reason, this study examines disclosed recommendations by fund-selling institutions on their webpages in 2015. Unlike previous studies which utilize fund inflows or net flows as a dependent variable, this study utilizes a dummy variable indicating a recommendation as a fund of the month as the dependent variable. This approach serves to circumvent the problem of information on new inflows for each class fund being unavailable since September of 2010. This approach also has the advantage of directly confirming recommendations by fund sellers.

III. Background and Hypothesis

A. Mutual Fund Market in Korea

This section explains the market structure of the mutual fund market. In South Korea, the net assets of mutual funds increased significantly between 2007 and 2008 and then declined until 2012. Since 2012, net assets in the mutual fund market began to rise again, but the net assets of equity funds decreased steadily until 2015.

As shown in Table 1, mutual funds can be classified into equity funds, hybrid bond funds, and fixed income funds for the purposes of this study. Usually, the levels of sales fees are similar within the same fund type, and differences in sales fee are considerable across different types of funds.

TABLE 1

TYPES OF MUTUAL FUNDS

Source: Korea Financial Investment Association (http://dis.kofia.or.kr, last accessed: 2015. 12. 7).

Table 2 shows the average sales fee according to the type of fund. The sales fee tends to increase when the fund invests in riskier assets. The derivative bond fund shows the highest average sales fee, at 0.823 percent, while the hybrid bond fund shows the lowest average sales fee of 0.281 percent. Accordingly, there is an incentive for fund sales personnel to promote riskier products to earn higher sales fees.

TABLE 2

SALES-RELATED COSTS ACCORDING TO VARIOUS FUND TYPES

Note: Management fees are fees that are paid out of the fund’s assets to the fund’s investment adviser for investment portfolio management.

Source: Korea Financial Investment Association (http://dis.kofia.or.kr, last accessed: 2015. 12. 7).

Certain studies, including that by Shin and Cho (2014), focus on equity mutual funds to examine the relationship between fund inflows and sales fee. This approach is used because it is difficult to compare various types of funds based on identical criteria. This paper also compares the sales compensation amounts within each mutual fund type, in this case domestic equity funds and hybrid bond funds.

B. Characteristics of Funds of the Month

1. Selection Criteria

Most financial institutions which sell mutual funds provide a recommendation list on their websites. This list, with a name in the form of “OO Bank (OO) recommended funds,” is selected by the internal recommended products council. They regularly select promising products through both quantitative and qualitative measures. Quantitative measures include past returns, fund age, AUM, and fund balance levels, among other measures, and qualitative evaluations are based on such factors as the operation strategies, post-administrative services, and the provision of information. The weights of the qualitative measures in the selection criteria vary depending on the institution. For example, Woori Bank announced that they assign a weight of 90 percent to quantitative measures and 10 percent to qualitative measures, while HMC Securities Corp. assigns a weight of 40 percent to qualitative measures.

2. Updating Period

Although financial institutions explicitly mention that the updating period of a recommendation list and the timing of updates are irregular, the lists generally change every month.6 Some products remain on the list even after an update. During the survey period of four months, the retention rates of previously selected funds remaining in the list were 85.4% and 85.9% among banks and security corporations, respectively. On the list of the financial institutions with affiliated asset management companies, 23% funds were products of affiliated firms among the banks and the 16% funds were from affiliated firms among the security corporations.

The recommended funds for each institution differ considerably. For example, when funds recommended by more than two institutions are defined as duplicated funds, the ratio of duplicated funds is only approximately 5.3% among banks.

3. Fund Classes and Types

The recommendation lists of fund-selling institutions include both online and offline funds. In particular, recommendation lists in the banking industry tend to include more products sold online, and the ratio of the CE class was highest, referring to funds sold online with no front-end commission. On the other hand, securities companies recommended more funds sold offline, and the ratio of A-Class funds, which incur a front-end commission and which also have small ongoing fees, was highest.

While all institutions recommended equity funds, the securities industry’s lists include more equity funds and derivative funds. On the other hand, the lists recommended by banks have a higher portion of hybrid bond funds and bond funds.

C. Research Question and Econometric Model

This study examines whether fund-selling companies tend to recommend products with higher sales fees or front-end load commissions to customers, testing the hypothesis below.

This study uses lists of what are referred to as funds of the month, which are recommended on the websites of fund-selling companies to identify recommendations by fund distributors. First, a simple comparative analysis is conducted to compare the sales fee amounts or front-end loads between recommended funds and non-recommended funds. This comparative analysis is performed separately for each share class and type. A-Class (one-time front-end load type) and C-Class (ongoing fee type) funds sold offline are analyzed, as they are the most common types of Korean mutual fund share classes. This study also undertakes a regression analysis to examine whether financial institutions tend to select funds with higher sales compensation rates as the ‘fund of the month,’ even after controlling for other characteristics such as past returns and the size of the fund.

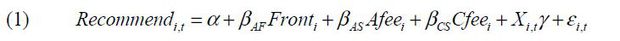

The econometric model is shown in equation (1), and an unbalanced random-effect panel logistic regression analysis is utilized.7 The dependent variable, Recommendi,t , has a value of one when fund i is recommended during the month of t by any fund sales institution. When the fund is not recommended at all, it has a value of zero.

Independent variables are sales personnel’s compensation amounts, in this case sales fees and front-end load commissions, represented by Fronti . As ongoing sales fees are higher in the C-Class fund than in the A-Class fund, Afeei and Cfeei are separately included, indicating sales fees of A-Class and C-Class, respectively.8 The analyses are separately conducted for domestic equity funds and hybrid bond funds, as past returns differ from one another. I add four control variables in the regression. These are the natural log of AUM (assets under management) to represent the size of a fund,9 fund age (natural log of the fund age calculated in units of years), past market-adjusted net returns,10 and the volatility of the previous rates of return. Time fixed effects are also included.

D. Data Collection Method

The lists of funds of the month were collected for five months from April 15 to August 18, 2015. The lists were collected manually from the webpages of 26 fund sales companies (nine banks and 17 securities companies) each week. A fund is classified as a recommended fund if it appeared on the list during the survey period.

The others are categorized as non-recommended funds. To rule out small-scale funds with no cash flow from the sample, funds with an AUM of less than one billion won in both March and April of 2015 were excluded. In addition, if a fund is less than one year old or if the past rate of returns is not available for a new fund, those funds are excluded. For domestic equity funds, index funds are excluded.

Information on fund sales fees and front-end loads was collected from the Korea Financial Investment Association’s homepage as of August 18, 2015. Past balances and fund ages were calculated using materials provided by Zeroin. Information on the monthly rate of return for calculating past performance was also provided by Zeroin.

Past performance as market-adjustment earnings is calculated based on early May of 2015 by subtracting the KOSPI rate from the previous rate of returns. Furthermore, abnormal rates of return over the past 18 months were also calculated using the three-element model of Fama and French (1992; 1993).11

E. Calculating Past Performances of Funds

In this study, we use 12-month market-adjusted returns in the regression analysis to indicate a funds’ past performance. Market-adjusted returns are net returns for which market indices are subtracted from the return of a fund. The market indices of domestic equity funds and hybrid bond funds are the KOSPI index and the KIS Index, respectively.

Meanwhile, 18-month abnormal returns are also utilized in the comparative analysis. Abnormal returns are calculated using market and scale factor information obtained from FnGuide’s DataGuide 5 and the KIS index.

Market-adjusted return can be easily calculated by market indices, but the performance of market indices cannot reflect normal expected returns. Thus, bias can arise when estimating excessive returns.12 On the other hand, abnormal returns can be measured by eliminating the influence of market factors, scale factors, value factors, period factors, and credit factors, but this method is not intuitive compared to market-adjusted returns.

IV. Comparative Analysis

In this section, the sales fee amounts and front-end loads are compared, as are the fund sizes and previous performance outcomes between recommended funds and non-recommended funds. I focus on A-Class and C-Class funds sold offline, which are domestic equity funds and hybrid bond funds. The significance test for the mean difference is in this case a one-sided T-test. For fund types with few observations, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test is also used, comparing the median values. The results of the Wilcoxon rank-sum test are shown in the Appendix, and the results are similar to those of the T-tests.

A. Amounts of Sales Compensation

Overall, the average sales compensation is higher for recommended funds than for non-recommended funds. Table 3 compares the funds on the recommended lists with all non-recommended funds in share class A. Among the domestic equity funds, the average ongoing sales fee is significantly higher for the recommended funds by 0.065 percentage points. The average front-end load is also higher in the recommended funds by 0.092 percentage points. Among the hybrid bond funds, the sales fee and front-end load amounts are both higher for the recommended funds, but the differences are not insignificant.

TABLE 3

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS: AVG. SALES FEE AND AVG. FRONT-END LOAD (A CLASS)

Note: 1) The numbers of observations of (recommended, non-recommended) funds are (32, 154) for domestic equity funds and (7, 18) for hybrid bond funds. 2) ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively. 3) Index funds are excluded from domestic equity funds.

Table 4 shows that the average sales fees for recommended funds are significantly higher for the hybrid bond funds, also showing that the average sales fee is higher for hybrid bond funds by 0.163 percentage points. The average sales fee is higher for recommended funds among domestic equity funds, but the difference is not significant.

TABLE 4

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS: AVG. SALES FEE (C CLASS)

Note: 1) The numbers of observations of (recommended, non-recommended) funds are (9, 77) for domestic equity funds and (7, 58) for hybrid bond funds. 2) ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively. 3) Index funds are excluded from domestic equity funds.

B. Assets Under Management and Past Performance

In the previous section, it was confirmed that funds recommended on the fund-selling companies’ webpages have higher sales fees or front-end loads than other funds. Next, we compare other characteristics to determine whether the recommended funds have other benefits to offset the high sales-related fees. In this section, we compare past AUM and past performance.

1. Assets Under Management (AUM)

Table 5 shows that the average AUM value is much higher for recommended funds than for non-recommended funds. Among domestic equity A-Class funds, the average past AUM levels amount to 183 billion won for recommended funds and 24.1 billion won for non-recommended funds. The difference in the average AUM remains very large regardless of the class type or type classification. Hence, it is confirmed that the size of the fund is an important criterion in the selection of the fund of the month for financial institutions.

TABLE 5

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS: AVG. AUM (ASSETS UNDER MANAGEMENT)

Note: 1) The value for AUM is calculated at the beginning of May of 2015. Funds which started after May of 2014 are excluded. 2) The numbers of observations of (recommended, non-recommended) funds among domestic equity funds are (32, 154), (10, 78) for A-Class and C-Class funds, respectively. The numbers of observations of (recommended, non-recommended) funds among hybrid bond funds are (7, 18) and (7, 60) for A-Class and C-Class funds, respectively.

In general, large-sized funds can set diverse operational strategies and reduce some costs. Therefore, it is considered reasonable for fund sellers to recommend large-scale funds. However, the large scale of recommended funds judged to be high in sales-related costs may stem from the fact that financial institutions have long recommended these funds. However, it is difficult to determine the cause of the size difference with currently available data.

2. Past Performance

As the form of remuneration varies according to the share class, even within the same type of fund, past net returns are compared at the share class level after the subtracting sales compensation amounts. According to the comparative analysis, recommended funds tend to have higher returns, but the differences in the past net returns become insignificant at the share class level.

In Table 6, the average past 12-month market-adjusted return and 18-month abnormal return for recommended funds are significantly higher before the sales cost deduction. However, when comparing net returns at the share class level, as shown in Table 7, the average past net return for recommended funds is only significantly higher with the 12-month market-adjusted return for hybrid bond funds.

TABLE 6

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS: PAST FUND PERFORMANCE (MANAGED FUND LEVEL)

Note: 1) Past returns are calculated at the point of May 4th, 2015. 2) Abnormal returns are estimated by alpha from the three-factor model of Fama and French (1993). For the market factor, the KOSPI index is used for equity funds and the KIS index is used for hybrid bond funds. 3) Market-adjusted returns are calculated by subtracting the KOSPI rate from the previous rate of returns. 4) For 12-month market-adjusted returns, the numbers of observations of (recommended, non-recommended) funds are (22, 198) for domestic equity funds and (6, 122) for hybrid bond funds. 5) For the 18-month abnormal returns, the numbers of observations of (recommended, non-recommended) funds are (17, 170) for domestic equity funds and (3, 108) for hybrid bond funds. 6) ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively.

TABLE 7

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS: PAST FUND PERFORMANCE (SHARE CLASS LEVEL)

Note: 1) Past returns are calculated at the point of May 4th, 2015. 2) Abnormal returns are estimated by alpha from the three-factor model of Fama and French (1993). For the market factor, the KOSPI index is used for equity funds and the KIS index is used for hybrid bond funds. 3) Market-adjusted returns are calculated by subtracting the KOSPI rate from the previous rate of returns. 4) For 12-month market-adjusted returns, the numbers of observations of (recommended, non-recommended) funds are A (32, 154) and C (9, 78) for domestic equity funds and A (7, 18) and C (7, 59) for hybrid bond funds. 5) For 18-month abnormal returns, the numbers of observations of (recommended, non-recommended) funds are A (30, 151) and C (8, 70) for domestic equity funds and A (5, 15) and C (6, 49) for hybrid bond funds. 6) ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively.

V. Regression Analysis

A. Descriptive Statistics

1. Summary Statistics

Table 8 shows the summary statistics of the sample for the regression analysis. Among all funds during the five months of the sample period, 11.3% and 10.9% of funds were recommended from among hybrid bond funds and domestic equity funds, respectively. Fund size refers to the natural log of assets under management, and Fund age is the natural log of the survival period based on the year. The means of Fund size and Fund age are both slightly larger for domestic equity funds. The number of A-Class funds, 95, is smaller than the number of C-Class funds, 320, among the hybrid bond funds, while the number of A-Class funds is twice as large as the number of C-Class funds among domestic equity funds. The average C-Class sales fee is slightly larger than the A-Class front-end load in both panels.

2. Correlation Tables

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between variables are presented in Table 9. As the funds are divided into two classes, A and C, the correlation coefficients are calculated for each class of funds. The explanatory variables, the front-end loads or the sales fees, have a significant positive correlation, except for C-Class funds among domestic equity funds. This implies that higher sales compensation amounts are related to a higher probability of being recommended by the fund-selling company. The front-end loads and sales fees for A-Class funds are positively correlated among domestic equity funds, whereas they are negatively correlated among hybrid bond funds.

TABLE 9

CORRELATION TABLES

Note: ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively.

Fund size is significantly correlated with the dependent variable in all cases. Fund size and fund age show a significantly positive correlation, reflecting that older funds have had enough time to obtain more inflow.

The VIF index for each variable is less than two, and there is no evidence that refutes multicollinearity between the variables.

B. Regression Results

1. Hybrid Bond Funds

In this section, the results of the regression analysis are presented. These results show that the amounts of sales-related costs have significant effects on the probability of a fund being selected as a fund of the month, even after controlling for other characteristics of the funds.

Table 10 shows the results of the estimation of equation (1) with the sample of hybrid bond funds. Columns (1)-(4) show positive and significant coefficients of the sales fees for the A-Class and C-Class funds. This indicates that high ongoing sales fees explain the probability of a fund being selected as a fund of the month from among other hybrid bond funds. This positive relationship between a recommendation and the sales cost is consistent with the findings of Siri and Tufano (1998), Christoffersen et al. (2013), and Shin and Cho (2014).

TABLE 10

REGRESSION: SALES COMPENSATION UPON A RECOMMENDATION FOR HYBRID BOND FUNDS I

Note: 1) New funds less than one year of age and small-scale funds with less than one billion won in March and April of 2015 were excluded. 2) Past 12-month market-adjusted returns are calculated using the KIS index, and it is share class level net return after subtracting sales compensation amounts. 3) ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively, and the numbers in ( ) are the robust standard errors.

The coefficient of the front-end load is also positive, but it is only significant in column (4), the model without the volatility of past returns and with time fixed effects. The results of the additional robustness checks are shown in the Appendix. Table A1 shows the results of the robustness check after adding management fees and brokerage fees and adjusting the sample size. The regression results show all positive, significant coefficients for the sales fees for the A-Class and C-Class funds.

The control variable, the fund size, shows significant and positive coefficients in all models (model (1), 2.795). This confirms that funds with larger AUM levels are more likely to be included on the recommendation list. The past 12-month market-adjusted return shows a significant coefficient only in column (4).

A-Class funds have two types of sales costs, while C-Class funds have only a sales fee. As the correlation table shows a significant correlation between a front-end load and a sales fee for A-Class funds, some studies use a variable which combines these sales costs instead of using two separate variables.

Table 11 shows the regression results using the variable of the A-Class sales cost, a combination of the sales fee and the front-end load for the A-Class funds. The coefficients of the A-Class sales cost and the C-Class sales fee remain positive and significant. According to the average marginal effect of the model (4), the probabilities of being recommended are increased by 2.83%p and 3.67%p, respectively, if the size of the sales cost for both A-Class funds and C-Class funds is increased by 0.1%p.

TABLE 11

REGRESSION: SALES COMPENSATION UPON A RECOMMENDATION FOR HYBRID BOND FUNDS II

Note: 1) New funds less than one year of age and small-scale funds with less than one billion won in March and April of 2015 were excluded. 2) Past 12-month market-adjusted returns are calculated using the KIS index, and they are the share class level net return after subtracting the sales compensation amount 3) ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively, and the numbers in ( ) are the robust standard errors.

2. Domestic Equity Funds

Table 12 reports the results the estimation of equation (1) with the sample of domestic equity funds. These results show positive and significant coefficients of the front-end load for A-Class funds and the sales fee for C-Class funds, as expected. The coefficients of the sales fee for A-Class funds are not significant, but they are still positive. Thus, funds with high sales compensation amounts are also more likely to be recommended as a fund of the month among domestic equity funds. Table A2 in the Appendix also verifies the positive effect of sales compensation on a recommendation even after management fees, brokerage fees, and adjusting for the sample size.

TABLE 12

REGRESSION: SALES COMPENSATION UPON A RECOMMENDATION FOR DOMESTIC EQUITY FUNDS I

Note: 1) Index funds are excluded. 2) New funds less than one year of age and small-scale funds with less than one billion won in March and April of 2015 were excluded. 3) Past 12-month market-adjusted returns are calculated using the KOSPI index, and the corresponding share class level net returns after subtracting sales compensation amounts. 4) ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively, and the numbers in ( ) are the robust standard errors.

Fund-scale factors in all models still show significant coefficients (model 1, 3.730). Moreover, unlike the hybrid bond funds above, the coefficient of the fund age shows a significant and negative value (model 1, -3.947), indicating that fund-selling companies tend to recommend relatively new funds. The coefficient of the 12-month market-adjusted return is insignificant.

In Table 13, even after accounting for the combined compensation of the front-end loads and sales fees for A-Class funds, the coefficients are still positive and significant. Thus, we can confirm that the funds higher sales-related costs are also the more likely to be selected as a fund of the month from among domestic equity funds. According to the average marginal effect in model (4), the probability of being recommended is increased by 1.02%p if the sales cost of A-Class funds is increased by 0.1%p.

TABLE 13

REGRESSION: SALES COMPENSATION UPON A RECOMMENDATION FOR DOMESTIC EQUITY FUNDS II

Note: 1) Index funds are excluded. 2) New funds less than one year of age and small-scale funds with less than one billion won in March and April of 2015 were excluded. 3) Past 12-month market-adjusted returns are calculated using the KOSPI index and the corresponding share class level net return after subtracting sales compensation amounts. 4) ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively, and the numbers in ( ) are the robust standard errors.

VI. Concluding Remarks

This study examined whether fund sellers tend to recommend funds with higher sales-related costs in Korea. This assessment is meaningful as there are not many recent studies which focus on this issue. For the analysis, we utilized the recommendation lists posted on actual financial institutions’ webpages as a ‘fund of the month.’ This approach is useful as the size of net inflows to mutual funds could not be identified at the share class fund level.

The averages of the sales fees and front-end loads of recommended funds and non-recommended funds are compared. The comparison is conducted for A-Class and C-Class funds among domestic equity funds and hybrid bond funds. The comparative analysis indicates that the recommended funds on the webpages have higher sales fees and front-end loads than the non-recommended funds. Moreover, past performance outcomes of recommended funds are not significantly superior to those of non-recommended funds at the class fund level after deducting sales-related costs.

The regression analysis results confirm that funds with higher sales fees tend to be selected by fund sellers as a fund of the month, even after controlling for the effects of size and past performance. The results of the regression analysis show that fund-selling companies are making efforts to maximize their sales compensation when creating the list of recommended funds.

As sales fees or commissions are directly related to the profit of the fund-selling institutions, it is natural for these companies to make efforts to realize high sales compensation. Therefore, it is necessary to establish proper regulations pertaining to disclosures or other behavioral obligations to mitigate such conflicts of interest so that the rational economic behavior of fund sellers does not infringe upon their consumers’ interests.

As this study examined only recommendation lists on webpages, there is a limitation when interpreting all recommendation services of actual fund sales channels with these results. For example, during the actual recommendation process, net inflows could be even higher in funds with greater sales fees. However, as this study could not utilize information about inflows, weighting according to inflow size was not utilized.

Furthermore, because these recommended fund lists as posted on the webpages are open to the public, objectively excellent funds may have also appeared on the webpages. It is also possible that with face-to-face recommendations, fund sales personnel can be more sensitive to sales compensation levels in these cases as compared to publicly disclosed lists. Another limitation here is that the data collection period was short at five months. The future performances of recommended funds are also unaddressed in this study, and it is possible that consumers pay high sales costs to sellers, anticipating high future returns. These tasks all remain for future researchers.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1

ROBUSTNESS CHECKS ON REGRESSION: HYBRID BOND FUNDS

Note: 1) New funds less than one year of age and small-scale funds with less than one billion won in March and April of 2015 were excluded. 2) In models 3 and 4, samples are adjusted by excluding funds with less than one billion won in June and July of 2015. 3) Past 12-month market-adjusted returns are calculated using the KOSPI index and the corresponding share class level net returns after subtracting sales compensation amounts. 4) ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively, and the numbers in ( ) are the robust standard errors.

TABLE A2

ROBUSTNESS CHECKS ON REGRESSION: DOMESTIC EQUITY FUNDS

Note: 1) Index funds are excluded. 2) New funds less than one year of age and small-scale funds with less than one billion won in March and April of 2015 were excluded. 2) In models 3 and 4, samples are adjusted by excluding funds with less than one billion won in June and July of 2015. 3) Past 12-month market-adjusted returns are calculated using the KOSPI index and the corresponding share class level net returns after subtracting sales compensation amounts. 4) ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively, and the numbers in ( ) are the robust standard errors.

TABLE A3

WILCOXON RANK-SUM TEST: MEDIAN SALES FEE AND FRONT-END LOAD (A CLASS)

Note: 1) The numbers of observations of (recommended, non-recommended) are (32, 154) for domestic equity funds and (7, 18) for hybrid bond funds. 2) ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance level, respectively. 3) Index funds are excluded from domestic equity funds.

TABLE A4

WILCOXON RANK-SUM TEST: MEDIAN SALES FEE (C CLASS)

Note: 1) The numbers of observations of (recommended, non-recommended) are (9, 77) for domestic equity funds and (7, 58) for hybrid bond funds. 2) ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively. 3) Index funds are excluded from domestic equity funds.

TABLE A5

WILCOXON RANK-SUM TEST: MEDIAN PAST FUND PERFORMANCE (SHARE CLASS LEVEL)

Note: 1) For the 12-month market-adjusted returns, the numbers of observations of (recommended, non-recommended) are A (32, 154) and C (9, 78) for domestic equity funds and A (7, 18) and C (7, 59) for hybrid bond funds. 2) For 18-month abnormal returns, the numbers of observations of (recommended, non-recommended) are A (30, 151) and C (8, 70) for domestic equity funds and A (5, 15) and C (6, 49) for hybrid bond funds. 3) Past returns are calculated at the point of May 4th, 2015. Abnormal returns are estimated by alpha from the three-factor model of Fama and French (1993). For the market factor, the KOSPI index is used for equity funds and the KIS index is used for hybrid bond funds. 4) ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively.

Notes

This paper is a revised and translated version of the chapter 3 of Oh (2015), Research Monograph 2015-06, Korea Development Institute.

Consumers may consider a recommendation service by banks or security companies to be free, and they do not want to pay separate fees for IFAs.

The forms of these fees also vary, from one-time front/back-end load commissions to ongoing annual maintenance fees.

Although the regression results in the appendix include variable for management fees and brokerage fees, they are not discussed further, as they are additional control variables.

For this analysis, it is necessary to assume that fund-selling institutions recommend funds from an online recommendation list to offline customers. Because financial institutions declare that their recommendation fund council selected the online list according to quantitative and qualitative criteria, an offline recommendation list would share the evaluation criteria. Therefore, it is considered reasonable to analyze online recommendation lists to evaluate conflicts of interest in the mutual fund market.

The Financial Investment Association does not provide separate information about inflows and outflows at the class level.

Ten out of twenty-six institutions have clearly stated that they update their recommendation lists every month.

The random effect model is used because the main regressor, sales compensation, is fixed while other control variables such as past returns and fund sizes change.

Front-end loads and sales fees may vary over time. Changes in the sales costs are disclosed on the website of KOFIA. However, these changes do not arise frequently, and there were no changes in the sample during this study. For this reason, the econometric model includes non-time-varying sales compensation.

This is calculated as the previous 12-month market-adjusted return at the point of the previous month.

We also calculated 12-month abnormal returns, and these results were similar to those for 18-month abnormal returns.

According to Brown and Warner (1980), the market-adjusted return rate implicitly regards all securities beta values as a type of market index, assuming that the expected return rate of the securities is identical to the expected return rate of the market index.

References

, , & . (2017). Understanding the Advice of Commissions-Motivated Agents: Evidence from the Indian Life Insurance Market. Review of Economics and Statistics, 99(1), 1-15, https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00625.

, & (1980). Measuring Security Price Performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 8(3), 205-258, https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(80)90002-1.

, , & (2013). What Do Consumers’ Fund Flows Maximize? Evidence from Their Brokers’ Incentives. The Journal of Finance, 68(1), 201-235, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2012.01798.x.

, & (1992). The Cross‐section of Expected Stock Returns. The Journal of Finance, 47(2), 427-465, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1992.tb04398.x.

, & (1993). Common Risk Factors in the Returns on Stocks and Bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 33(1), 3-56, https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(93)90023-5.

. (1982). Moral Hazard in Teams. The Bell Journal of Economics, 13(2), 324-340, https://doi.org/10.2307/3003457.

Korea Financial Investment Association. Korea Financial Investment Association, http://dis.kofia.or.kr, last accessed: 2015. 12. 7.

, & . (2014). Determinants of Fund Investment Flows: Asymmetry between Fund Inflows and Fund Outflows. KDI Journal of Economic Policy, 36(4), 33-69, in Korean, https://doi.org/10.23895/kdijep.2014.36.4.33.

, & . (1998). Costly Search and Mutual Fund Flows. Journal of Finance, 53(5), 1589-1622, https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00066.