- P-ISSN 2586-2995

- E-ISSN 2586-4130

This paper investigates the sales process of treasury stocks, while most previous research studies treasury stock repurchases. The sales of treasury stocks are an important measure to protect management rights only in Korea, as Korea’s laws and systems allow treasury stock sales according to the board’s resolution and not by the decisions made at the general shareholders’ meetings. The board’s resolution, which considers the owner-manager’s interest on management rights, can cause damages to small shareholders. Considering (i) the economic characteristics of treasury stocks, (ii) other countries’ institutions and experiences, (iii) a theoretical assessment of the possibility of small shareholder losses, and (iv) lessons from Korea’s actual instances, Korea’s present system should be corrected at least in the mid and long term. Even in the short-term, rules pertaining to sales enacted by the board’s resolution inducing small shareholder losses should be overhauled. The autonomous discipline by various stakeholders could be an ideal measure by which to monitor owner-manager’s decisions. In addition, temporary intervention measures, such as government examinations, could be implemented to protect small shareholders.

Treasury Stock, Management Right, Corporate Governance

K22, G34, G38

In this paper, I examine the role of treasury stock ‘sales’ with regard to protecting management rights. There have been numerous existing research works on stock repurchases, and a considerable number of papers have studied the relationship between repurchasing stocks and the protection of management rights. However, research aimed directly at treasury stock sales is rare,1 possibly because most repurchased stocks are instantly retired and not kept in the firm in many countries, including the U.S.

In Korea, unlike in other countries, treasury stock sales play a key role in protecting management rights.2 One example is a designated sale of treasury stocks to a friendly group, who vote in favor of an owner-manager.3 When splitting a company off à la an equity spinoff, Korea’s Commercial Act allows the allocation of new firm’s stock to an existing firm in proportion to its treasury stock shares. Thus, the equity spinoff, in which treasury stocks are involved, would be a useful scheme to retain, protect, and transfer management rights.

Essentially, a stock repurchase is a means of delivering economic benefits to general shareholders.4 When a firm repurchases its own stocks, shareholders who accept the repurchase offer can convert their shares into cash. In this sense, stock repurchases have the same economic meaning as dividend payments.5 However, stock repurchases in Korea have a different objective. Korean firms rarely incinerate repurchased stocks, unlike firms in other countries. Moreover, we can find numerous cases in which firms sell treasury stocks to a third party in favor of a dominant stockholder. These designated sales only considering the dominant stockholder’s interests can damage small shareholders’ interests, and such possibilities have already been reported.6 These experiences have made treasury stock sales one of the most pressing issues in the area of corporate governance in Korea. As a result, multiple bills, which I will thoroughly examine later in this work, have been proposed in the National Assembly of Korea to amend the management system of treasury stocks. Thus, studies of the legal aspects and the economic effects of designated sales of treasury stocks are urgent.

Given this urgency, this paper theoretically analyzes how the sales of treasury stocks are used to protect management rights and how this affects small shareholders’ interests.7 The theoretical model incorporates an owner-manager’s problem, in which he manages treasury stocks to maximize his own interest. Obviously, the owner-manager’s managing policy of treasury stocks affects other stockholders’ interests. Subsequently, I investigate and interpret several real-world instances based upon a theoretical analysis. This work also examines several countries’ institutions as they pertain to treasury stocks and attempts to find a solution to overhaul Korea’s institution in terms of corporate governance.

This paper starts by checking the mechanism of management rights protection using treasury stocks. I contrast the repurchasing-and-reselling process with the repurchasing-retiring-and-issuing process.8 In the former process, which many Korean firms have adopted, the treasury stocks can be protective of management rights, unlike in the latter process. This is possible because Korea’s current law intends a discrepancy between the two schemes, which I will explain in Sections II and VI. I also contrast Korea’s institution of treasury stocks with those of other countries and explain why treasury stocks play a vital role in protecting management rights in Korea’s institutional and historical context.

In the fourth section, I analyze the sales process of treasury stocks. Through a theoretical analysis, I formulize when sales of treasury stocks are harmful to small shareholders and when protecting management rights via the sales of treasury stocks can be beneficial to them. To identify these conditions, I consider a synergy effect from integrated management, investment efficiency, and a control premium for the dominant stockholder. In addition to theory, investigating actual instances can concretize situations in which small shareholders experience losses. In Section V, I list several cases of treasury stock sales, explain the transaction processes in detail, and analyze the economic effects on the interested parties. From the examinations of theory and actual instances, I can provide certain hints with regard to an overhaul of the institutions of treasury stocks. In the last part of the paper, I assess a few bills proposed in the National Assembly of Korea and look for a plan to convert the insight gained through the analysis offered here into implementable policies.

Unfortunately, most existing studies focus on “stock repurchases” and not “stock sales,” which is the main topic in this paper. The only exception, to the best of the knowledge of the author, is the study of Kim and Lim (2017), which empirically analyzes the motives behind treasury stock sales. However, some “stock repurchases” works are also directly related to this paper, especially if they deal with management right issues. These papers, including Shin and Kim (2010), Jung and Kim (2013), and many other works, will be examined later in this section.

This review section begins with the research on the motives behind stock repurchases, and there are a few such motives which are often mentioned. The first motive is known as the leverage hypothesis, in which firms utilize stock repurchases to adjust firm leverage levels. Repurchasing the firm’s own stocks reduces equity capital and thus increases the debt-to-equity ratio. Firms can take managerial advantage such as a reduction of corporate taxes given the high debt-to-equity ratio (Masulis, 1980). When a firm calculates an optimal debt-to-equity ratio and the actual ratio is less than the optimal level, the firm may repurchase stocks to meet the optimality condition (Dittmar, 2000). The literature on Korean firms agrees with the leverage hypothesis on the whole. Yoon, Kim, and Lee (2004) showed that firms with a low leverage ratio repurchased stocks more often. Lee and Joo (2005), Lee and Lee (2006), and Kim, Cha, and Jeong (2012) found similar results.

The second stream in the literature considers a stock repurchase as a tool to deliver financial compensation to relevant shareholders. The dividend substitution hypothesis explains that firms want to pay dividends at a stable level and thus use stock repurchases to spend additional earnings (Bajaj and Vijh, 1990).9 For some reasons, a firm’s value can be under-evaluated, and the firm may want to send a signal about this under-valued situation to the stock market (the under-evaluation hypothesis). If the signal is understood well, the firm’s stock price will rise (Comment and Jarrell, 1991). The tax-saving hypothesis suggests that stock repurchases are preferred to dividends if the income tax rate for dividends is greater than the capital gain tax rate (Ofer and Thakor, 1987).

Studies on the Korean economy on financial compensation via stock repurchases do not display a consensus, unlike in the leverage hypothesis. Yoon, Kim, and Lee (2004) obtained negative results for the dividend substitution hypothesis and the under-evaluation hypothesis. Lee and Joo (2005) added a negative result for the under-evaluation hypothesis. Lee and Lee (2006) and Kim, Cha, and Jeong (2012) found results which did not support the dividend substitution hypothesis, whereas the under-evaluation hypothesis was supported. These results implicitly suggest that stock repurchases in Korea are implemented for several different purposes in addition to the financial compensation motive.10

Another stream in the literature on motives for stock repurchases seeks these motives by examining owner-manager’s tunneling behaviors. The free-cash-flow hypothesis explains a mechanism that consumes part of the cash flow via stock repurchases, which can prevent an owner-manager from abusing the firm’s resources (Jensen, 1986; Nohel and Tarhan, 1998). Inversely, an owner-manager can exploit stock repurchases to take private gains. If he has significant shares, including stock options, he has an incentive to raise stock prices via stock repurchases. This is known as the opportunism hypothesis (Fried, 2001).

With regard to the free-cash-flow hypothesis, most studies in the Korean literature have found supportive results. Yoon, Kim, and Lee (2004), Lee and Joo (2005), Lee and Lee (2006), and Kim, Cha, and Jeong (2012) confirmed this hypothesis by analyzing data form Korean firms. Byun and Pyo (2006) showed that the opportunism hypothesis was upheld in their analysis of large shareholders’ stock sales.

The last stream in the motive research is about the protection of management rights, which is the main concern in this paper. Bagnoli, Gordon, and Lipman (1989) theoretically argued that a firm’s value may be over-evaluated when the firm repurchased its own stocks. Thus, taking over a firm that repurchased stocks may produce smaller return than desired by the taker. Harris and Raviv (1988) and Stulz (1988) illustrated a process consisting of a stock repurchase, a stock price rise, and a takeover cost increase. In addition, the cost can be magnified when the stock repurchase is carried out by debt financing. Bagwell (1991) explains a mechanism by which the takeover cost increases, when the stock repurchase reduces outstanding stocks, especially when it exhausts stocks with low asking prices. Then, a potential bidder for management rights experiences a significant increase in the takeover cost and the transaction cost.

Yoon, Kim, and Lee (2004) empirically tested a hypothesis which held that small firms tend to repurchase stocks to protect their management rights, but they could not obtain a decisive result. The hypothesis that a firm whose manager does not have sufficient shares would repurchase stocks, suggested by Lee and Joo (2005), is also not supported by empirical tests. Lee and Lee (2006) examined the causal relationship between the owner-manager’s shares or foreigners’ shares and stock repurchases, though their results supported the management rights protection hypothesis only partially.11 Unlike the papers discussed above, Kim, Cha, and Jeong (2012) found that the fewer shares an owner-manager owns, the more often stock repurchases occur.

The study by Shin and Kim (2010), which directly focused on the relationship between stock repurchases and management rights protection, examined several variables, such as the dominant stockholder’s shares, the share difference between the largest and the second largest shareholders, ownership structures, and the personal characteristics of dominant stockholders. In addition, Shin and Kim (2010) derived a result which showed that stock repurchases were utilized for management rights protection, also showing that there was some potential to damage small shareholders’ interests. Jung and Kim (2013) showed that fewer stock repurchases were implemented when firms had additional management rights protection tools such as supermajority voting and a golden parachute. This result argues indirectly that stock repurchases can be used for management rights protection. Wang, Song, and Kim (2014) discovered that non-controlling large shareholders sell stocks when their firms repurchase stocks. Their study did not prove that stock repurchases were carried out for the protection of management rights, but it showed that stock repurchases could discourage takeover bidders.

In the last part of the previous section, I presented theories and several studies of stock repurchases for the protection of management rights. This section explains the protection mechanism of sales (and possession) of treasury stocks, in addition to the previously discussed stock repurchases.

Youn (2005) summarized the protection mechanisms as follows: (i) stock repurchases in the open market increase the dominant stockholder’s voting share,12 (ii) stock repurchases exhaust outstanding stocks, which increases takeover costs, and (iii) repurchased stocks can be sold to friendly groups when a threat to management rights exists. The first two mechanisms are activated merely by buying stocks, but the last one arises only when selling stocks. Youn (2005), who acknowledged the importance of treasury stock sales in terms of management rights protection, empirically tested the management rights protection hypothesis considering the possession of one’s own stocks, as well as stock repurchases. Unfortunately, the test could not obtain a positive result which supported the hypothesis. Kim and Lim (2017) conducted the most unique work which investigated the relationship between management rights protection and treasury stock sales, to the best of the author’s knowledge. From an empirical assessment, this study found that companies with good governance incinerated repurchased stocks more often, while companies with bad governance sold more treasury stocks. These sales would be for the protection of management rights.

Henceforth, I explain in detail the mechanism by which the designated sales of treasury stocks serve as a management rights protection tool. Once stock repurchases are implemented, the number of outstanding stocks decreases by the repurchased amount, which could be kept or retired. In contrast, both issuing new stocks and selling the repurchased stocks increase outstanding stocks, giving the company money or assets in return for the (out-bound) stocks. Theoretically, the process of repurchasing stocks, retiring them, and issuing new stocks is identical to the process of repurchasing stocks and reselling them. Essentially, stock prices reflect the firm value and the number of outstanding stocks, and both treasury stock sales and new stock issuances have the same impact on the number of outstanding stocks and the recruited amount of money. If there is a dilution effect of new stock issuances, we can also expect the same effect in the case of treasury stock sales.

In Korea, there is a significant difference between treasury stock sales and new stock issuances, in both legal and institutional terms. Article 342 in Korea’s Commercial Act allows firms to sell their own stocks upon a resolution by the board of directors.13 This implies that any firm, more specifically, the board of the firm, can sell its treasury stocks to whomever it chooses. Owing to this allowance, Korean firms can use the designated sales of treasury stocks as a management rights protection tool. On the new stock issuance side, Article 418 in the aforementioned Act requires a guarantee of existing shareholders’ (proportional) rights. When a firm issues new stocks, it should allot proportionally the new stocks to existing shareholders.14 Thus, the new stock issuance cannot be used as a protection tool.

Why do these two processes with identical circumstances economically differ institutionally? It is known that the 2011 revision of Korea’s Commercial Act originally intended to reconcile the treasury stock sales process and the new stock issuance process.15, 16 This means that legislators likely understood the rule on treasury stock sales, made in the actual revision, and knew it precisely. Therefore, the 2011 legislation would respond to the necessity to discriminate the treasury stock sales process from the new stock issuance process.

The judicial precedents confirm the intentions behind the legislation. In 2015, Samsung C&T Corporation (hereinafter Samsung C&T) and Cheil Industries Inc. (hereinafter Cheil Industries) merged. During the merger process, Samsung C&T sold its treasury stocks to KCC which declared its support for the merger, but Elliot Management Corporation (hereinafter Elliot) applied for an injunction against the treasury stock sale. Elliot argued that the sale violated the principle of shareholder equality, which should be considered during the issuance of new stocks. The court, however, approved the sale, as Article 342 in Korea’s Commercial Act allowed such a sale. The court also explained that there had been numerous discussions of the sales process of treasury stocks in relation to earlier legislation during the revision processes, but meaningful changes remained elusive.17 Thus, the court understood that the legislators of the current Act intended to support Article 342 without any changes.

If a firm simply wants to collect new funds, there is no reason to distinguish between the process of treasury stock sales and the process of new stock issuances. Thus, the main role of the distinctive treatment between two processes is to make the third-party allotment of treasury stocks possible. Note that the current legal system in Korea allows the board of directors to choose the buying side, implying that the owner-manager can choose their partner at will.18 To sum up, we can understand that Article 342 allows a firm to use treasury stocks to protect management rights.

If treasury stocks are sold to a specific party, the voting power of all existing shareholders decreases. At times, however, it becomes possible for every party involved to benefit due to the designated sales of treasury stocks, despite the losses of existing shareholders’ proportional rights. For example, existing shareholders may welcome treasury stock sales if a third party creates major business synergy with the firm which sells its stocks. In this paper, I will also examine the economic effect of treasury stock sales which create such a synergy effect, as well as the economic implication of such processes. However, typically the designated sale of treasury stocks disappoints some stockholders.

Before proceeding to the next section, I examine the legal aspects of treasury stock sales further. The legal reasons which hold that two processes are treated equally are that (i) they have identical economic characteristics, and (ii) both are capital transactions under business accounting standards. The funds (or assets) obtained from treasury stock sales are posted as a capital surplus. In this view, court decisions which consider a transaction involving treasury stocks as a profit-and-loss transaction are incorrect (An, 2011; Song, 2014).

On the other hand, the two processes should be distinguished also because stockholders’ gains from transactions involving treasury stocks are reflective and collateral benefit stemming from the firm’s business decisions. The firm or board does not need to protect this type of benefit. In other words, the benefit is not significant enough to restrict the asset management decisions of firms. Following this logic, the court may uphold its view that transactions involving treasury stocks are indeed profit-and-loss transactions and that there is no need to guarantee preemptive rights to new stocks by existing shareholders (Lee, 2006).

In terms of the profit-and-loss transactions, treasury stocks have economic value, akin to cash or gold, for instance. That is, the buying and selling of treasury stocks do not differ from the buying and selling of gold, and thus both types of financial decisions could be carried out upon a resolution by the board. However, treasury stocks have no economic value (footnote 9). Only if we consider the economic characteristics of the treasury stocks, we should consider them as capital transactions.

In this section, I investigate institutions with regard to treasury stocks in the U.S., Japan, Germany, and UK and examine treasury stock laws and practices in each country. To describe how these institutions handle treasury stocks, we need to explain three phases with regard to the management of treasury stocks: buying, retaining, and selling. Although this paper’s main concern is on selling these types of stocks, the regulations affecting the buying and retaining of these stocks are also important when attempting to understand the mechanisms in place which attempt to protect management rights with regard to the use of treasury stocks. After examining other countries’ institutions, I compare the findings to the situation in Korea, especially with regard to the Commercial Act revised in 2011 and the Capital Market Act. This comparison reveals the institutional and historical contexts about why and how treasury stocks play a vital role in protecting management rights in Korea.

The U.S. is one of the most generous countries with regard to the managing and regulating of treasury stocks. The U.S. Model Business Corporation Act allows stock repurchases in principle and only regulates funding plans, i.e., stock repurchases should not be financed by debt (Article 6.31).19, 20 It is believed that debt financing could harm the company’s financial condition, and thus harm small shareholders’ interests. Rule 10b-18 of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission also imposes specific conditions on stock repurchases but allows stock trades via the capital market in general.21 Korea’s Commercial Act, revised in 2011, is quite similar to the U.S. Model Business Corporation Act in terms of stock repurchases. In Korea, there are no meaningful regulations on stock repurchases besides a similar funding restriction for these repurchases.

With reference to the possession and sales of treasury stocks, each state has its own practices. In California, repurchased stocks should be retired.22, 23 In New York and Delaware, the possession of treasury stocks is allowed, and the sales process follows the new stock issuance process as a whole,24 but certain decisions such as sales prices are delegated to the board of directors. For a clearer understanding of the treasury stock sales practices in the U.S., it is necessary to examine court decisions. U.S. court precedents appear to respect existing shareholders’ preemptive rights, and they have prohibited treasury stock sales as a means by which to change the existing ownership structure. 25 That is, the designated sales of treasury stocks to protect management rights were not allowed in court decisions and precedents.

With regard to treasury stock sales, Korea’s Commercial Act is similar to the laws in New York and Delaware, which adopt traditional legal capital rules. Under these laws, treasury stock sales by board resolutions are allowed in principle. Kim (2006), however, points out that some U.S. legislation, including the Model Business Corporation Act, has abolished the traditional rules, now, disallowing the possession of treasury stocks.

Japan drastically changed their treasury stock management system with the revision of their Commercial Act in 2001. At the time, the possession of treasury stocks was allowed in principle, and also allowed were arbitrary sales decisions by boards of directors (Commercial Act 2001, Article 211.1) However, the sales process should follow the new stock issuance process (the above Act, Article 211.3), because the sales of treasury stocks and the new stock issuance are considered to be identical in terms of their economic characteristics.26, 27

Chung (2015) argued that the revision of Korea’s Commercial Act was significantly affected by Japanese law due to (i) the change from prohibiting the possession of treasury stocks to allowing their possession, and (ii) the delegation of a significant role to the board of directors.28

Korea’s system for treasury stock sales, however, is much more generous to the owner-manager of the firm compared to the law in Japan. The board can decide upon the sales process at will, unlike in Japan, and the preemptive rights of existing shareholders do not have to be respected. This additional generosity presents the appearance that the legislation could be a result of lobbying, as the owner-manager can now use treasury stock sales as a management protection tool according to this legislation.

In the U.K., stock repurchases are prohibited in principle (Companies Act 2006, Article 658.1). The U.K., however, has added exceptions and has relaxed regulations on stock repurchases.29 Until 1980, the U.K.’s court precedents did not allow any types of stock repurchases. In 1980, the country revised the Companies Act to incorporate a prohibition clause for stock repurchases. In 1981, stock repurchases were allowed only with permission granted during a general shareholders’ meeting.30 In 1985, the newly revised Companies Act allowed stock repurchases upon a resolution by the board, and only if the articles of association of the firm approved the resolution (the above Act 1985, Article 690.1).

For treasury stock sales, Article 560.2.b of the Act explicitly admits the preemptive right of existing shareholders, indicating that the sales process differs from that in Korea, in which the board can decide the details of treasury stock sales, including who will buy the stocks.

Germany also prohibits stock repurchases in principle, like the U.K. Germany’s Stock Law (Aktiengesetz), enacted in 1937, approved only a few exceptional stock repurchases. The number of exceptions, however, was increased through the revised Stock Law in 1978 and through the Corporate Law actions in 1985 and 2009.31 It is important to note the cases in which stock repurchases are allowed: (i) stock repurchases not exceeding 10% of issued stocks with permission granted during a general shareholders’ meeting, and (ii) stock repurchases under significant, direct, and desperate circumstances. It is known that stock repurchases in Germany do not occur often, but the regulation was relaxed recently.

With regard to treasury stock sales, Article 53a in the Stock Law respects the preemptive rights of existing stockholders and declares the principle of shareholder equality.

The experiences of the U.S., Japan, U.K. and Germany confirm that treasury stocks cannot be used as a management protection tool, except in a few instances in the U.S. and in Europe (in EU countries), while also prohibiting stock repurchases in principle.32, 33 Under these regulations, it is difficult for an owner-manager who controls the board to use treasury stocks to protect his management rights.

With regard to treasury stock sales, nearly all countries except for a few states in the U.S. demand that the sales process should follow the process of new stock issuances. In the U.S., a recent trend is to require the retiring of the repurchased stocks. Even when allowing the possession of repurchased stocks, the sales process should follow the process of new stock issuances. A few states which maintain traditional legal capital rules, including Delaware, respect the preemptive rights of existing shareholders, even in a loose sense. This was established by court precedents in earlier times. In addition, the U.S. has various tools to protect small shareholders, such as class action lawsuits. They can use these tools in order to make up for their losses when a resolution by the board causes some damage to them. Such a system could preemptively discipline the board and prevent them from making malicious decisions using treasury stocks.

From these examples in the U.S. and Japan, we learn that relaxing regulations on stock repurchases is not enough for treasury stocks to become a management protection measure. More important than relaxation would be whether or not to admit the preemptive rights of existing shareholders. Except for a few states in the U.S. which have well-organized civil compensation schemes, we cannot find any case to distinguish the treasury stock sales process from the new stock issuance process. Only Korea’s Commercial Act distinguishes between the two processes.

In the next section, I present a theoretical model in which I examine the economic effects of treasury stock sales by means of board resolutions, focusing especially on the economic effects on each stakeholder associated with the firm. This examination of the economic effects provides some defense for utilizing treasury stocks as a management rights protection tool. When the synergy effect of integrated management is strong enough, management rights protection via treasury stock sales may be beneficial to small shareholders as well.

Consider two firms: termed here 1 and 2. A person, a large shareholder (denoted as L in this section), has shares l1 of firm 1, and shares l2 of firm 2. Suppose that L is managing both firms; that is, this entity controls both boards. The other shareholders, such as small shareholders (denoted as S here), collectively own shares s1 of firm 1 and s2 of firm 2. The firms also have their own stocks, with t1 and t2 denoting each firm’s own shares. It is also assumed that there are no other shares; that is, li + si + ti = 1 for each i.34

Initially, L enjoys (pecuniary or non-pecuniary) benefits by managing the firms. The control premiums for each corresponding firm are denoted here as p1 and p2 . The premium in each case exclusively belongs to the current manager.

Suppose that firm 1 can earn π1 when it operates normally. Firm 2 can also earn π2 . When firm 1 uses its investment funds to buy the treasury stocks of firm 2, firm 1 earns only φ. It is also assumed that π1 ≥ φ + t2π2 . The assumption implies that firm 1 can earn during normal operation more than when it uses its funds on firm 2 because the acquisition of firm 2’s shares can occur at any time. Hence, better or at least equally valued opportunities may exist.

If a person manages both firms simultaneously, synergy may be realized via this type of integrated management scheme.35 The synergy adds α1 to the value of firm 1 and α2 to the value of firm 2.36 Under the single-firm management scheme, the firms respectively earn π1 and π2 . Under the integrated management scheme, firm 1 earns π1 + α1 or φ + α1 and firm 2 earns π2 + α2 .

First, consider a situation without any threat to the management rights of firm 2. In this case, integrated management is better for both L and S unless the synergy effects are zero. Each firm can earn more with the integrated management scheme. This model does not consider the possibility of tunneling by L (that is, an owner-manager).

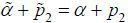

Second, the owner-manager faces a threat to the management rights of firm 2 and should

therefore choose between the relinquishment of management rights and the protection

of these rights by buying the treasury stocks of firm 2 using the investment money

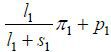

of firm 1. When relinquishing management rights, L obtains  from firm 1 and

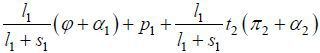

from firm 1 and  from firm 2. When protecting these rights, L obtains

from firm 2. When protecting these rights, L obtains  from firm 1 and l2(π2 + α2) + p2 from firm 2.

from firm 1 and l2(π2 + α2) + p2 from firm 2.

L considers (i) the effect of synergy stemming from the integrated management scheme (α1 and α2), (ii) the size of the control premium for firm 2 (p2), and (iii) the efficiency loss from losing an investment opportunity (π1 − φ). Although the efficiency loss is not ignorable, L would choose to protect the management rights of firm 2 exploiting the investment funds of firm 1 if the synergy effect and the control premium are large enough.

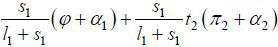

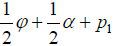

At this time, I check the payoffs for S. When L does not protect the management rights of firm 2, S obtains  from firm 1 and

from firm 1 and  from firm 2. When protecting the management rights, S can obtain

from firm 2. When protecting the management rights, S can obtain  from firm 1 and s2(π2 + α2) from firm 2.

from firm 1 and s2(π2 + α2) from firm 2.

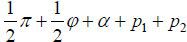

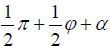

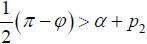

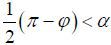

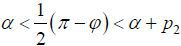

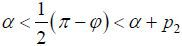

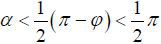

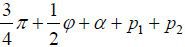

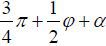

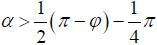

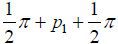

To simplify the discussion, assume that the shares of L, S, and the treasury shares amount correspondingly to one third,37 π1 = π2 ≡ π , and α1 = α2 ≡ α. Hence, L obtains  in the protection case and π + p1 in the non-protection case. Thus, L wants to protect management rights if

in the protection case and π + p1 in the non-protection case. Thus, L wants to protect management rights if  . That is, L allows the efficiency loss and takes the treasury stocks of firm 2 using the investment

funds of firm 1 if the efficiency loss is less than the sum of the synergy effect

and the control premium for firm 2.

. That is, L allows the efficiency loss and takes the treasury stocks of firm 2 using the investment

funds of firm 1 if the efficiency loss is less than the sum of the synergy effect

and the control premium for firm 2.

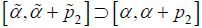

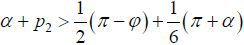

The payoffs for S depend on the decision by L. When L does not protect the management rights of firm 2, S receives π ( for the shareholders of firm 1 and

for the shareholders of firm 1 and  for those of firm 2). When protecting management rights, S obtains

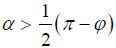

for those of firm 2). When protecting management rights, S obtains  . Thus, S is better when L protects management rights if

. Thus, S is better when L protects management rights if  . If

. If  , S prefers not to protect the management rights. The important aspect here is that S considers only the synergy effect of integrated management and the efficiency loss

incurred when losing investment opportunities, unlike L, who also considers the size of the control premium.

, S prefers not to protect the management rights. The important aspect here is that S considers only the synergy effect of integrated management and the efficiency loss

incurred when losing investment opportunities, unlike L, who also considers the size of the control premium.

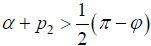

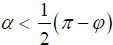

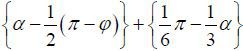

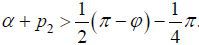

In summary, we have three regions where the interests of L and S exhibit different patterns. In  , L relinquishes the management rights, and there is no damage to S. There exists a major efficiency loss which forces L to give up these rights; thus, S is not exploited by the greed of L. In

, L relinquishes the management rights, and there is no damage to S. There exists a major efficiency loss which forces L to give up these rights; thus, S is not exploited by the greed of L. In  , L protects the management rights. This protection benefits S because the efficiency loss is not very large. In the third region,

, L protects the management rights. This protection benefits S because the efficiency loss is not very large. In the third region,  , L protects management rights, which generates damage to S. The size of efficiency loss is not ignorable and in fact is greater than the synergy

effect. L, however, protects the management rights considering the control premium. These results

are summarized in Figure 1.

, L protects management rights, which generates damage to S. The size of efficiency loss is not ignorable and in fact is greater than the synergy

effect. L, however, protects the management rights considering the control premium. These results

are summarized in Figure 1.

Thus far, I have discussed the interests of S as a whole while not distinguishing between the shareholders of firm 1 from those

of firm 2. Obviously, the two groups may include different persons. In the non-protection

case, the shareholders of firm 1 and those of firm 2 receive  , respectively. In the protection case, S of firm 1 obtain

, respectively. In the protection case, S of firm 1 obtain  , and S of firm 2 receive

, and S of firm 2 receive  . Because

. Because  , S of firm 1 will be better only if α is large enough. S of firm 2 will be better also only if α is large enough, because their shares are reduced from

, S of firm 1 will be better only if α is large enough. S of firm 2 will be better also only if α is large enough, because their shares are reduced from  to

to  .

.

It is important to check the region of  in detail, where the protection of management rights leads to losses for S, because

in detail, where the protection of management rights leads to losses for S, because  , π > 2α. For S of firm 2, they receive better payoffs in the non-protection case because they obtain

, π > 2α. For S of firm 2, they receive better payoffs in the non-protection case because they obtain

when management rights are protected and

when management rights are protected and  when these rights are not protected. Under this condition, L protects the management rights, and hence S of firm 2 suffer losses. The synergy effect is not enough to make up for the dilution

effect on their reduced shares.

when these rights are not protected. Under this condition, L protects the management rights, and hence S of firm 2 suffer losses. The synergy effect is not enough to make up for the dilution

effect on their reduced shares.

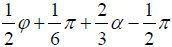

For S of firm 1, the gains or losses are not obvious. The difference in the payoffs between

the protection case and the non-protection case is  that is

that is  . The first term is negative, and the second term is positive. It is important to

note that S for both firms are damaged if the first term dominates the second term.

. The first term is negative, and the second term is positive. It is important to

note that S for both firms are damaged if the first term dominates the second term.

Additional Discussion

Given the above discussions, I uncovered the possibility that S would experience losses given the decision by L. This possibility arises even when L only (legally) exploits the resources of firm 1 and does not utilize illegal instruments such as tunneling. Henceforth, I extend the discussion to the additional scenarios of illegal tunneling, successful investments using money from treasury stock sales, and others.

First, we examine the case of illegal tunneling by L. At this stage, L would consider tunneling when calculating the size of the control premium. That is,

p2 increases and the interval of [α, α + p2] therefore expands. As shown above, when the size of the efficiency loss,  , is in the interval described above, L protects the management rights of firm 2 and S incur losses. Thus, illegal tunneling increases the possibility of damage to S.

, is in the interval described above, L protects the management rights of firm 2 and S incur losses. Thus, illegal tunneling increases the possibility of damage to S.

In the second case, tunneling decreases the firm value. While tunneling increases the controlling shareholder’s profits, it would violate the firm’s value. That is, π + α could be reduced due to tunneling. For simplicity, we assume that tunneling reduces α38 and that a change of α does not affect the size of p2. Given that the tragedy which befalls S occurs with the probability assigned in the interval, [α, α + p2], the possibility of this tragedy may increase or may not depending on the distribution of the efficiency loss (π − α). If the efficiency loss is distributed uniformly and independently of α, a change of α does not affect this possibility because the length of p2 remains the same. On the condition that L protects the management rights, the possibility of tragedy befalling S could increase. Under the reduced α, the possibility of protection definitely decreases, but the possibility of a tragedy for S likely remains at a similar level (Figure 2).

In fact, tunneling can be one of the major considerations for L. If tunneling reduces the value of the firm and increases the control premium as well, we should consider two cases the above together. This leads to a more of a possibility of a tragedy for S.

Third, I examine the case in which money obtained from treasury stock sales increases the value of firm 2. The previous model does not consider revenue from treasury stock sales. These sales, however, provide money (or assets in kind), even when they are urgently carried out under a threat affecting management rights.39 Obviously, the newly injected money would increase the value of the firm in general.

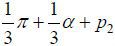

At this stage, the new value of firm 2 is ψ, which is greater than π. I assume that  . This is the case if the increase in the firm value precisely reflects the increase

in circulated stocks.40 Similar to the previous analysis, we know that the payoff for L is π + p1 in the non-protection case and

. This is the case if the increase in the firm value precisely reflects the increase

in circulated stocks.40 Similar to the previous analysis, we know that the payoff for L is π + p1 in the non-protection case and  in the protection case. This implies that L protects the rights of firm 2 when

in the protection case. This implies that L protects the rights of firm 2 when  For S, they receive π in the non-protection case and

For S, they receive π in the non-protection case and  in the protection case. Thus, protection benefits S if

in the protection case. Thus, protection benefits S if  Compared to the basic analysis, the possibility that protection leads to larger payoffs

for both L and S increases. This is a fairly obvious result, as the value of firm 2 increases. However,

there is still the possibility that the decision by L will harm S. The probability may or may not increase according to the distribution of π − φ. When the efficiency loss is uniformly distributed, the probability of a tragedy

for S is identical to that in the basic model.

Compared to the basic analysis, the possibility that protection leads to larger payoffs

for both L and S increases. This is a fairly obvious result, as the value of firm 2 increases. However,

there is still the possibility that the decision by L will harm S. The probability may or may not increase according to the distribution of π − φ. When the efficiency loss is uniformly distributed, the probability of a tragedy

for S is identical to that in the basic model.

Fourth, I check the possibility that treasury stock sales cannot create proper value. That is, we assume that  .41 At this time, sales cannot increase the value of firm 2 in proportion to the increase

in outstanding stocks. When

.41 At this time, sales cannot increase the value of firm 2 in proportion to the increase

in outstanding stocks. When  , management rights protection could be more rational compared to that in the basic

model but less rational compared to the third extension. On the other hand, the fact

that firm 2 does not take reasonable compensation would mean that firm 1 can gain

additional benefits. This in turn implies a larger value of φ and thus a smaller value of π − φ. The reduced efficiency loss explains that management rights protection could be

rationalized more easily.

, management rights protection could be more rational compared to that in the basic

model but less rational compared to the third extension. On the other hand, the fact

that firm 2 does not take reasonable compensation would mean that firm 1 can gain

additional benefits. This in turn implies a larger value of φ and thus a smaller value of π − φ. The reduced efficiency loss explains that management rights protection could be

rationalized more easily.

The fifth case is such that the synergy effect by integrated management is endogenously linked to the willingness

of L to protect management rights. Suppose that a firm has a sudden and urgent necessity to protect its management

rights. To meet this necessity, L would mobilize affiliates’ funds. The mobilized affiliates may have, however, no

business synergy with the firm in crisis or may have some synergy. In fact, if a firm

in a large conglomerate has a great amount of synergy with other affiliated firms,

the firms may already have share relationship, such as parent-subsidiary firms. Thus,

there is a strong presumption that the newly appeared savior, who has funds to spare,

has little synergy with the desperate firm. In such a case, a smaller α may imply a larger p2; that is, L may want to protect the management rights of firm 2 despite the exceedingly low synergy

effect. Under this specification, I denote the new synergy effect and the new control

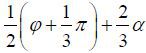

premium as  and

and  , respectively, and these are correlated with each other. I also assume that

, respectively, and these are correlated with each other. I also assume that  .42 Because

.42 Because  ,

,  . That is, the possibility of a tragedy befalling S increases in this new situation.

. That is, the possibility of a tragedy befalling S increases in this new situation.

We can think of another case in which the firm 2’s value increases after a take-over. This occurs when a newly introduced manager is more competent than an existing manager. A take-over may occur when the existing manager does not run the firm well. In fact, one of the greatest examples of damage from the management rights protection for S is losing an opportunity to take a good manager via a take-over.

If the new manager significantly improves the firm value, L willingly relinquishes the management rights and S would welcome the take-over. If the new manager’s ability is somewhat limited and does not cover the control premium, L protects management rights. This leads to losses for S.

When the new manager increases the value of the firm, the firm earns more; that is, π and π − φ increase. Figure 3 shows that the protection would occur less often when π − φ increases depending on the distribution of α. If α is distributed uniformly and independently of π − φ, the probability of protection decreases and the probability of a loss for S increases conditional on the presence of protection.

The last discussion is about a white knight.43 Until now, I have discussed on the sales from one affiliated firm to another affiliated firm in one conglomerate. A white knight, which is not an affiliated firm, cannot make a synergy with the threatened firm.44 Moreover, the control premium does not belong to the white knight. Therefore, the sale to the white knight is only possible when the purchase of treasury stocks is profitable enough to the white knight (or the manager of the white knight). This indicates that the threatened firm should guarantee a sufficient payoff to the white knight. It is highly likely that this guarantee harms S of the threatened firm.

When the white knight takes over the treasury shares for firm 2, L takes  from firm 1 and

from firm 1 and  from firm 2. If L does not protect management rights, L receives

from firm 2. If L does not protect management rights, L receives  . Thus, L of the threatened firm sells treasury stocks to the white knight if

. Thus, L of the threatened firm sells treasury stocks to the white knight if  . Compared to the decision standard in the basic model, L requires a larger value of α or a greater p2 to protect management rights, as some part of the earnings of firm 2 and the synergy

effect from the integrated management scheme goes to the white knight. The second

term on the right hand side in the above case of inequality is the leaked value to

the white knight.

. Compared to the decision standard in the basic model, L requires a larger value of α or a greater p2 to protect management rights, as some part of the earnings of firm 2 and the synergy

effect from the integrated management scheme goes to the white knight. The second

term on the right hand side in the above case of inequality is the leaked value to

the white knight.

For S of the threatened firm, the payoff decreases from  to

to  when L sells the treasury stocks for firm 2 to the white knight. If the synergy effect is

not large enough, the sale leads to losses for S. It is important to note that L would sell treasury stocks to the white knight only if the control premium (p2) is sufficiently large. If the synergy effect (α) is not large enough, S must experience losses, which is highly probable. On the other hand, S of firm 1 obtains

when L sells the treasury stocks for firm 2 to the white knight. If the synergy effect is

not large enough, the sale leads to losses for S. It is important to note that L would sell treasury stocks to the white knight only if the control premium (p2) is sufficiently large. If the synergy effect (α) is not large enough, S must experience losses, which is highly probable. On the other hand, S of firm 1 obtains  when treasury stocks are not sold and

when treasury stocks are not sold and  when these stocks are sold. That is, they realize a better payoff when L sells the treasury stocks of the firm 2 to the white knight.45

when these stocks are sold. That is, they realize a better payoff when L sells the treasury stocks of the firm 2 to the white knight.45

In this section, I present some real-world cases of treasury stock sales. When discussing these cases, I infer the objectives of the sales and determine the economic effects on the stakeholders, especially the small shareholders. The theoretical analysis in the previous section suggests that each case can be evaluated by (i) measuring the size of the synergy effect when using the integrated management scheme, and (ii) calculating the size of the efficiency loss incurred when losing other investment opportunities. In addition, we should gauge the size of the control premium. Unfortunately, this paper does not assess concrete figures but instead formulates plausible storylines to evaluate each item, as follows.

The first instance is the occasion in which Hyundai Motor Company (hereinafter HMC) sold its treasury stocks to Incheon Steel46 in March of 2001. This case consisted of two trades. First, HMC paid 294.8 billion won to Incheon Steel for 9.74% shares of Kia Motors which had been owned by Incheon Steel. Second, Incheon Steel paid 185.7 billion won to HMC for its treasury stocks (in an amount of 4.87%). Thus, Incheon Steel did not use any money. The trades are summarized as follows: Incheon Steel’s shares for Kia Motors were exchanged for HMC’s treasury stocks and 109.1 billion won (Figure 4).

Kia Motors was acquired in 1998 by the Hyundai Motor Group (hereinafter HMG). Thus, it was necessary to raise shares for Kia Motors and related firms so as to strengthen the controlling power of the HMG owner. The trade currently being examined enhanced the owner-manager’s controlling power for HMC by empowering its treasury stocks with voting rights. The shares for Kia Motors were merely re-positioned.

We can evaluate this trade in terms of the theory introduced in the previous section. First, we can expect considerable business synergy, as HMC, Kia Motors, and Incheon Steel are closely linked in terms of their production processes. Incheon Steel provides production materials to HMC and Kia Motors, and both HMC and Kia Motors produce cars. Both car companies could enjoy economies of scale and offer a well-differentiated lineup of products through integrated decision-making processes. This synergy among these companies suggests that the treasury stock trade would be beneficial to not only for the owner-manager but also for small shareholders.

Second, we analyze the investment efficiency for the buyer firm, Incheon Steel in this case. Incheon Steel disposed of their shares in Kia Motors and secured the share of HMC and 109.1 billion won in cash. Given that the synergy between Incheon Steel and Kia Motors and HMC is not very distinctive, the investment would not be harmful to Incheon Steel.

Third, the trade results on the side of HMC would not be satisfactory. HMC paid 294.8 billion won and took the shares of Kia Motors. We can expect that HMC realized some synergy by taking the shares of Kia Motors, but the shares originally belonged to Incheon Steel, an affiliate of HMG; therefore, there would be no additional opportunities to enhance the integrated decision-making process. Moreover, HMC could not sell the shares of Kia Motors so that the owner of HMG could retain his control of Kia Motors. Therefore, the purchase of noncurrent assets would not be very appropriate in terms of opportunity cost. One additional item to note is that the treasury stock sale empowered HMC’s treasury stocks with voting rights. The owner-manager of HMG could increase his voting rights for HMC, thus damaging the proportional rights of small shareholders. The possibility of small shareholder losses suggests that the size of the control premium cannot be ignored for the owner-manager. Indeed, the control power for HMC, Kia Motors, Incheon Steel, and Hyundai Mobis, which constitutes a circular shareholding structure, is extremely important in controlling the whole of HMG. Therefore, the control premium for HMC could not be small.

In fact, the trade did not intend only to enhance the control of HMC but also aimed at governance restructuring of HMG overall. This implies that the trade may not consider investment efficiency as a top priority. This possibility becomes more evident when examining the following trades.

The actual reason why Incheon Steel sold its shares of Kia Motors is that Kia Motors took over the shares of Incheon Steel from HMC on that day. Due to the prohibition of cross-shareholding in Korea, Incheon Steel should dispose of its shares in Kia Motors. HMC should also dispose of its shares in Incheon Steel by selling them to Kia Motors in order to sell its treasury stocks to Incheon Steel.

Before the trade, HMC owned shares in both Incheon Steel and Kia Motors, and Incheon Steel held stocks in Kia Motors. After the trade, circular shareholding arose as Incheon Steel owned HMC, which owned Kia Motors, which owned Incheon Steel again. The change is summarized in Figure 5.

According to Lim and Jun (2009) and Yang and Cho (2014), circular shareholding does not carry any actually existing capital such as treasury stocks; therefore, it severely violates the principle of capital adequacy and creates fictitious voting rights, which reduces small shareholders’ actual voting rights. Thus, the trades among HMC, Kia Motors, and Incheon Steel would bring about nonignorable damage to small shareholders’ proportional rights.

In summary, we should consider both (i) the infringement of small shareholders’ rights and (ii) the owner-manager’s concern over controlling the entire business group in addition to the opportunity cost associated with HMC investment funds when evaluating the trade between HMC and Incheon Steel.

For a detailed analysis of small shareholders’ gains or losses in this case, it is necessary to know what the investment opportunities considered by HMC were and what business perspectives Kia Motors took, including their investment plans, financing strategies, and payout schemes, as well as other detailed elements. Here, I will not make such a detailed assessment. I can, however, conclude that the trade has non-ignorable possibilities of small shareholders’ losses and that the owner-manager would consider the control premium as more than a trifling issue.

After Mong-hun Chung, the owner-manager of the Hyundai Group, passed away in 2003, foreign investors bought stocks in Hyundai Elevator (hereinafter HE) aggressively. HE decided to sell its treasury stocks (in an amount of 7.67%) to six companies, including KCC; these stocks were owned by the family of the founder of the Hyundai Group, Ju-yung Chung, but were not affiliated with the Hyundai Group any longer, in order to protect its management rights.

The buyer firms were not affiliated with the Hyundai Group and there was therefore no synergy effect from any integrated management scheme. In addition, there was no control premium for the buyers, as they would not participate in managing HE. Thus, we can guess that they would not buy the shares of HE if there were better investment opportunities.47 That is, we can expect that HE would offer significant benefits. If this is the case, there would be no damage to the small shareholders of the buyer firms.

With regard to the selling firm’s gains or losses, we can expect the possibility of losses. The treasury stock sales of HE may not have been a well-planned trade; indeed it was a ‘rushed sale.’ Thus, the sale price would be discounted,48 or non-pecuniary offers would be provided. In addition, it was difficult to expect that the money obtained from the sale would be used overly appropriately.

For the small shareholders of HE, they lost some of their proportional rights when the treasury stocks were empowered with 7.68% voting rights. However, these losses would not been made up sufficiently. The newly secured funds would not be enough, and it would not be easy for HE to find satisfactory investment opportunities.

In July of 2006, Hyundai Express purchased HE’s treasury shares in an amount of 65.97 billion won. Because the two firms were operating in very different business areas, the business synergy would not be very significant. Hyundai Express, a logistics firm, would have some synergy with any firm in general, but integrated management with HE would not produce extra effects other than general synergy.

On the other hand, the control premium for HE would be very large, as HE was a critical player in the governing of the Hyundai Group overall;49 moreover, HE itself was a large-scale business. In other words, the control premium for HE included the control premium for the Hyundai Group overall.

At this stage, we examine the investment efficiency for Hyundai Express. The takeover of treasury stocks in HE by Hyundai Express was not a normal investment, indeed it was done to protect management rights for HE and for the reorganization of the governance structure of the Hyundai Group. Therefore, it was highly likely that the investment was not profitable. This discussion suggests that the treasury stock trade mainly concerned the control premium for HE, rather than the efficient utilization of idle money of Hyundai Express. And such concern would harm interests of the small shareholders of HE and Hyundai Express.

Moreover, the treasury stock sale was accompanied by a trade between HE and Hyundai Merchant Marine (hereinafter HMM). On that day, HMM paid 25.54 billion won to HE and took 18.67% of shares in Hyundai Express owned by HE. In order for Hyundai Express to buy the treasury shares in HE, HE should dispose of its shares in Hyundai Express due to the prohibition on cross-shareholding. Three months later, Hyundai Express issued new stock and HMM paid 14.4 billion won for this new stock issuance. These trades are summarized in Figure 6.

The trades summarized in Figure 6 drastically changed the governance structure of the Hyundai Group. The structure originally possessed many doubly and triply connected shareholding relationships, including an instance of circular shareholding. The newly changed structure removed several multiple connections and re-organized the governance structure in the form of a chain with a few multiple connections. The new structure, however, included one additional instance of circular shareholding in the form of Hyundai Express-HE-HMM, which would do severe damage to the proportional rights of the small shareholders of relevant companies. Figure 7 and Figure 8 compare the situation before and after the reorganization.

In April of 2008, HMC Investment Securities (hereinafter HMC IS) sold its treasury shares at a level of 8.65% to HMC, Kia Motors, Hyundai Mobis, Hyundai Steel, and Hyundai AMCO, which are core affiliates of HMG.

The trade involved a preceding trade. HMG acquired 29.76% of the shares of Shinheung Securities in January of 2008 and changed the company’s name to HMC IS. HMG increased its share amount to 38.41% with the above treasury share trade, as HMG considered that an amount of 29.76% of the shares was not enough to maintain proper control over its rights.

In fact, it cannot be expected that the above trades brought meaningful synergy effects to the companies involved. The core part of the trades is that the engaged companies were chosen because they had idle funds. Thus, those involved would experience losses from the viewpoint of opportunity cost. They could use the money for more valuable investment opportunities, but the investment was adequately satisfactory to the owner-manager, who wanted to launch a financial business.

The treasury share sale did not occur under an urgent threat of control rights. Instead, the sale was for preemptive purposes to strengthen the control rights of a newly acquired firm. Thus, the small shareholders of HMC IS would not experience losses, if the treasury stocks were not sold at a discounted price.

In June of 2014, Samsung SDI (hereinafter SDI) and Cheil Industries disposed of their treasury shares in Samsung Electronics (hereinafter SE). SE paid 34.42 billion won to SDI and 14.3 billion won to Cheil Industries. SE originally held shares at an amount of 20.4% in SDI while holding no stocks in Cheil Industries. Thus, the merger of the two firms (SDI and Cheil Industries) would decrease SE’s shares in the merged company to 13.5%. To maintain their control rights for SDI, SE bought all of the treasury shares owned by SDI and Cheil Industries, and SE secured shares in an amount of 19.6% in the newly merged SDI.

First, we examine the synergy among the three involved companies. Because both SDI and Cheil Industries produce electronic materials and parts, the synergy with SE would not be small. Second, the control premium for SDI was not insignificant either. SDI played an important role on the lower rungs of the ownership structure of the Samsung Group. The group’s ownership structure around SDI was as follows: Samsung Everland-Samsung Life Insurance (hereinafter SLI)-SE-SDI-multiple affiliates. This implies that the control rights for SDI critically influenced the control aspects of the Samsung Group.

The investment efficiency of SE, however, could not be satisfactory. To invest nearly 50 billion won in the affiliates’ shares would be somewhat wasteful considering that it would be difficult to sell the shares off.

To determine whether the trade generated gains or losses for the small shareholders of SE, we should compare the synergy effect with the investment inefficiency as described above. Moreover, the owner-manager of SE, who concerned over the control premium for SDI, could buy the shares of the affiliates, despite the fact that the investment inefficiency was greater than the synergy effect.

In June of 2014, Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance (hereinafter SFMI) sold 4% of its treasury shares to SLI, and took 4.79% of Samsung C&T’s shares, owned by SLI, and 41.7 billion won (Figure 9).

This trade was one of SLI’s share-transactions in which SLI disposed of shares of non-financial affiliates and increased their shares in financial affiliates. The structure change, however, did not create any vicious share relationships such as circular shareholdings, which differs from the previous cases of HMC and HE.

The synergy between SLI and SFMI would be significantly large, because they operated similar insurance businesses. On the side of SLI, the securement of SFMI’s shares using Samsung C&T’s shares would not be harmful. It could dispose of the shares of Samsung C&T, which would not produce any synergy with SLI. On the side of SFMI, the newly obtained shares of Samsung C&T would not be very valuable, and we should consider that the size of the outstanding stocks increased and small shareholders’ proportional rights were therefore damaged.

The owner-manager, however, would not consider only the synergy effect and the investment efficiency, but also the control premium for SFMI and Samsung C&T.

SE purchased 10% of the treasury shares of Cheil Worldwide in November of 2014. The purchase price was 22.08 billion won. Unlike other treasury stock sales by the Samsung Group, this trade was not connected to other transactions.

SE, an electronic company, would not have considerable synergy with Cheil Worldwide, an advertising company. SE may have better investment opportunities at more than 20 billion won than the securement of shares in Cheil Worldwide.

Thus, the treasury stock sale by Cheil Worldwide may generate (i) losses for small shareholders of SE because they lose better investment opportunities, and (ii) damage to the proportional rights of the small shareholders of Cheil Worldwide. Of course, the damage to the small shareholders could be recovered if Cheil Worldwide used the newly recruited funds properly.

Samsung C&T sold its treasury shares (5.76%, 64.7 billion won) to KCC, a white knight. The trade was a ‘rushed sale’ to handle Elliot’s opposition to the merger of Samsung C&T and Cheil Industries.

The story and details are quite similar to those associated with HE’s treasury stock sales in 2003, as both are cases in which white knights took over treasury stocks. There was no synergy with the white knight, and the white knight could not enjoy a control premium. The proportional rights of the small shareholders of Samsung C&T may have been damaged.

In this section, I reviewed several cases of treasury stock sales à la the previous section’s theoretical approach. A treasury stock sale could be beneficial to small shareholders as well as to the owner-manager. The small shareholders of the buying firm can gain benefits when the synergy effect with the selling firm is large enough. In the trade between SLI and SMFI, the small shareholders of SLI would enjoy some benefits given that the trade strengthened the relationship with SMFI, which could provide a significant synergy effect.

However, it would be more common for the small shareholders to experience losses. These types of sales, mainly concerning a control premium, could harm the small shareholders of both the buying firm and the selling firm. In addition, the small shareholders of the selling firm would experience losses in their proportional rights. They would thus lose some of their voting power.

The ‘rushed sale’ to protect the management rights can reduce the value of the firm, if the seller discounts the stock price or offers some non-pecuniary benefits to the buying firm. In the cases of HE and Samsung C&T, both firms disposed of their treasury shares to white knights in a hurry. For the small shareholders of the buying firm, taking the affiliate’s shares could not be the best investment decision given that such assets do not have sufficient liquidity. If the owner-manager wants to retain control rights to the selling firm, the buying firm should retain the shares. For example, SE purchased the shares of Cheil Worldwide, and SE needed to retain the stocks to maintain management rights over Cheil Worldwide. In fact, the acquisition would not realize significant synergy from the integrated management of SE and Cheil Worldwide. From the viewpoint of SE and the small shareholders of SE, the investment may not be very appropriate. Moreover, such an inappropriate investment could create losses in the form of opportunity costs.

However, it is highly likely that the instances in this section would bring benefits to the owner-manager, who is also the decision maker. These trades actually occurred. The decision makers can calculate their gains and losses thoroughly. However, it is difficult to determine whether small shareholders would realize gains or losses. In this paper, I examine only certain possibilities for gains and losses.

This examination can be performed in a more precise manner, if we have more relevant data. The synergy between two firms could be calculated from the inter-industry relationships, the trading volume between the two firms, and the sizes of the economies of scale, among other factors. The investment earning rate, stock earning rate, Tobin’s q, and several management indices can serve as proxies for the investment efficiency of the buying firm. For the losses of proportional rights, we can utilize the amounts of the decrease in the voting rights after the treasury stock sales.

Using the above variables, we can formulate several guidelines, formulas, indices, or check lists. Offering these to small shareholders, potential shareholder, and stock market participants in treasury stock sales cases could relieve small shareholders’ losses and could affect owner-managers’ decisions.

When I discussed the nature of treasury stock sales, I suggested that treasury stock sales for the protection of management rights would be disciplined in the long term. This contention is consistent with the economic characteristics of treasury stock sales. However, current institutions and the current legal system could be maintained if we consider the synergy effects. Even in this case, trades leading to losses by small shareholders should be regulated. Of course, such regulations would be designed so as not to disturb policy goals and to preserve the synergy effect. Thus, measuring small shareholders’ losses and comparing these losses with the positive synergy effect are important tasks. In the next section, I examine the policy implications in more detail and check a few bills which have been proposed in the National Assembly of Korea.

Before discussing policy measures to discipline treasury stock sales, here we examine the role of treasury stocks in the equity spinoff process, which is one of the most pertinent recent issues related to the management rights transfers. Note that many proposed bills to amend the Commercial Act deal with equity spinoff cases. This paper focuses on the mechanism by which treasury stock sales protect management rights, but the legal perspectives of treasury stocks, informed by treasury stock sales research, could be applied to equity spinoff cases in the same fashion.

In equity spinoff cases, in which one company is divided into two companies such as a holding company (mostly an existing and continuing legal entity) and an operating company (mostly a newly established legal entity), existing shareholders receive shares in both companies in proportion to their existing share ratios. Imagine that a company issues eighteen stocks and A and B have nine stocks each. If the company is split off and a newly established company issues six stocks, A and B will then each take three stocks of the newly established company. At this point, suppose that the company, not yet split, purchases six stocks, three from A and three from B. The company then has six stocks; A has six, and B has six. The voting rights of A and B are each 0.5, as treasury stocks do not have voting rights, but the new stocks for the newly established company are allotted to A, B, and the existing company: two to A, two to B, and two to the existing company. In summary, the new stocks are assigned to the treasury shares owned by the existing company. Thus, the owner-manager can increase his voting rights during the equity spinoff process if the existing company possesses treasury stocks.

Yoon (2015b) argues that the allotment of new stocks to treasury shares is not reasonable given that the ownership structure of the newly established company may differ simply in terms of whether or not treasury shares exist. Yoo (2014) also suggests that new stocks should not be allotted to the treasury shares to ensure consistency in the management of the legal system; treasury shares should not have voting rights in any case.

In fact, discussions centering on the allotment of new stocks should occur and should consider the legal aspects as they pertain to treasury stocks. The current legal system and precedents in the court consider a trade of treasury stock as a profit-and-loss transaction. From the perspective of a profit-and-loss transaction, the treasury stocks owned by the issuing company have economic value. The behavior by which the company buys treasury stocks is equivalent to the behavior by which the company buys gold, land, or machines. The company which possesses treasury shares has rights equal to those of outside shareholders whose stocks have economic value.

Song (2014), however, argues that treasury stocks have no economic value. Earlier in the paper, I also explained the economic characteristics of treasury stocks. Economically, the treasury stocks in the possession of the issuing company are ‘not-yet-issued stocks.’ Thus, it is obvious that they have no economic value. Considering that a trade in treasury stocks is a capital transaction, the right to claim new stocks by treasury shares is denied during the process of an equity spinoff. We cannot put economic value where there is no economic value.

In the handling treasury stock sales, the focus of this paper, the current legal system considers these sales as profit-and-loss transactions. The sales decisions for gold, land, or machines are delegated to the board of directors. Thus, the sales of treasury stocks can be determined by the board as well, meaning that we should consider both problems of treasury stock sales and of new stock allotments simultaneously when we fix the current system for better treasury stock management. If the system for treasury stock sales is fixed in order to prevent losses by small shareholders, the system for new stock allotments during equity spinoffs should be fixed as well.

Henceforth, we assess two proposed bills to amend the Commercial Act. The first is a bill that was proposed by Yongjin Park and other members of the National Assembly in Korea in July of 2016. The bill prohibits the allocation of new stocks for treasury shares. In addition, the existing company should discard its treasury shares when the equity spinoff process begins. The intention of this legislation was to fix the current system, which creates an asymmetric effect on the ownership structure among shareholders. Although the bill considers that treasury stocks do not have economic value and thus demands the removal of treasury stocks during an equity spinoff, it does not refute Article 342, which allows board resolutions on treasury stock sales. Putting no economic value on treasury stocks means that treasury stock trades are capital transactions. In this case, Article 342 should be revised, and treasury stock sales should follow the new stock issuance process. In conclusion, the bill does not consider legal consistency carefully.

The second bill to be examined was proposed by Youngsun Park and other members of the National Assembly in June of 2016. This bill targets Article 342 directly. It adds Article 342 ②, which requires that “treasury stocks should be disposed of in proportion to the existing shares.” Thus, this revision can be understood as meaning that the preemptive rights of the existing shareholders must be guaranteed. The bill, however, does not attempt to revise Article 418. This is a precise reversal to the previously examined bill by Yongjin Park. By the same logic, the two articles should be fixed simultaneously.

In addition to these two bills, many similar bills have been proposed. All of these bills consider the possibility of small shareholder losses and introduce measures to remedy these losses. None of the proposed amendments, however, express a solid understanding of the economic characteristics of treasury stocks fully, akin to how the current legal system misunderstands treasury stocks.

On the other hand, there are logical reasons to oppose the revision of the current system. The first is that the current legal system does not provide any effective means by which to protect management rights, except through the use of treasury shares. Choi (2016) states that revising the Commercial Act on treasury stock management should be done along with the introduction of other measures to bolster management rights protection.50 In such a case, why should we protect management rights? If a foreign speculative capital fund (or company), which pursues short-term profits, attacks domestic firms, management rights protection could be helpful to the national economy. Moreover, there is no guarantee that a new manager would improve the value of the firm. The new manager also has a private interest, as exemplified in the description of tunneling earlier in the paper.

However, this argument should answer the following questions. The first question asks why management rights protection is needed, even allowing for damage to small shareholders. The second asks whether the use of treasury shares for management rights protection is the best option, despite the fact that such protection is worthwhile in some situations. Yoon (2015a) argues that treasury stock sales according to a resolution by the board are too excessively protective in favor of the owner-manager, although the necessity of measures to protect management rights is accepted.

The second argument supporting the current system is that the relaxation of treasury stock management is a worldwide trend. Indeed, regulations pertaining to treasury stock management have been eased in the EU, Japan, and in other countries. EU countries have expanded the exceptions for conditions on treasury stock sales. Japan turned the policy perspective into an allowance in principle. The goal of these relaxation efforts, however, is to assist the financial management of firms, not to ensure management rights protection. The discussions in Section III explain that managing treasury stocks in relation to small shareholder losses has been strictly regulated in all countries, including those of the EU and Japan.

Considering (i) the economic and legal characteristics of treasury stocks, (ii) the proposed bills to revise the Commercial Act, and (iii) the logic for and against the current system, the current system for treasury stock management should be corrected in the mid and long term. Clearly, such a correction should be in good agreement with the economic characteristics of treasury stocks and should prevent damage to small shareholders.