Effect of Consulting on Microcredit Repayment in Korea†

Abstract

This study examines the effect of a one-on-one outsourced pre-lending consulting service on the repayment behavior of microcredit borrowers in Korea with administrative data from the Smile Microcredit Bank. A random change in the cut-off loan amount for mandatory consulting is utilized as an identification strategy. This three-day pre-lending business consulting service is effective in encouraging repayment behavior of existing businesses but it has no significant effect on start-up loans. The effectiveness of the consulting service in deterring delinquency with regard to existing loans is greater among male borrowers than among females.

Keywords

Microcredit, Non-financial Service, Consulting, Loan, Repayment, Arrear

JEL Code

D1, G21, J1, L3, N25

I. Introduction

Since Muhammad Yunus initiated the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh in 1976, several developed countries have introduced microcredit businesses as well to ease financial exclusion in their countries. In Korea, microcredit programs were started around the year 2000 by small non-governmental organizations such as the Joyful Union and the Social Solidarity Bank. After the global financial crisis, around 2010, the Korean government launched various political microcredit products,1 including the Smile Microcredit Bank (SMB). The SMB provides low-interest loans ranging from 2% to 4.5% to people with poor credit ratings2 (grades 7-10) or to those with low incomes.3

Although the SMB has grown through a government initiative, it is a non-profit organization whose source of funding consists of deposits in dormant accounts and donations. The SMB also provides business development services, as other typical microfinance institutions (MFIs) do. However, some critics argue that the government-led SMB is limited in terms of its business operations. The most salient critiques refer to its lackluster non-financial business development services.

The non-financial business development services include business training, consulting and mentoring. These services are commonly regarded as key functions to support the self-help of borrowers. The SMB requires that some borrowers undergo outsourced three-day one-on-one business consulting. Since the late 2012, it has also operated one-day business training programs in limited regions: Seoul and Busan. Nevertheless, non-financial support by the SMB continues to lag behind that offered by its counterparts in other advanced countries or even in developing countries. Thus, the SMB must strengthen its business development services, but this would require them to incur considerable operating costs. Therefore, a careful study should be conducted to determine how to extend such services; should the bank offer the same services to a larger number of people or should it revise the lineup of its services that are currently available?

As a first step, the current pre-lending consulting services need to be evaluated. To that end, this paper attempts to answer the following questions using administrative data from the SMB. First, could outsourced pre-lending business consulting increase the probability of repaying on time? Second, which borrowers benefit most from consulting? These questions could best be answered with a randomized controlled treatment akin to that in Karlan and Valdivia (2011). However, applying such a randomized controlled treatment in Korea and in other advanced economies is not practically feasible due to ethical issues. Therefore, this method cannot be applied to the current data on SMB borrowers.

Fortunately, however, the SMB has changed the rules pertaining to consulting requirements. Once loan applicants meet the criteria, they must receive one-on-one consulting provided by an outsourced institution before they can take out loans. The SMB has changed the consulting requirement rules at random points in time. Thus, this paper takes an advantage of these random changes to assess the effect of pre-lending consulting on reducing instances of arrears.

In fact, the ultimate long-term goal of MFIs would be to help clients increase their profit or income. Thus, the effects of consulting are best explained by analyzing profits, as in Mel et al. (2014) and McKernan (2002). Unfortunately, however, such an analysis is not possible because the SMB has no available information on the business performance or income of its clients. Given that the near-term primary objective of MFIs is to ensure timely repayments, the question as to whether or not a borrower will fall into arrears becomes a key concern for MFIs. Accordingly, it is important to verify whether pre-lending business consulting has any effects on preventing instances of arrears. Furthermore, microcredit users can repay their principle and interest on schedule only when they earn stable income. Therefore, arrears or the lack thereof can be a good indicator of he clients’ income status. In this sense, it is meaningful to analyze the effects of consulting on repayment behavior. Thus, this paper analyzes the effects of consulting, expanding the literature on business development services provided by MFIs (Mel et al. 2014; McKernan 2002; Halder 2003; Karlan and Valdivia 2011).

Moreover, this research can identify the factors behind situations in which a debtor is in arrears as they arise with regard to microcredit in advanced countries, as these factors exhibit distinctly different characteristics from those of developing countries. Microcredit pursues two fundamentally incompatible goals. Thus, it is critical for microcredit institutions to devise an effective repayment management mechanism to ensure their sustainability while at the same time to explore ways to reach out to the financially disadvantaged. Group lending based on social ties and peer monitoring is common in developing countries with advanced microfinance systems. However, this technique is not applicable to urban clients in advanced economies, who tend to be individualistic. In light of such a difference, it is necessary to find an appropriate approach that could work in advanced countries. This paper aims to analyze whether non-financial services such as consulting can promote repayment behaviors in a relatively developed country, Korea. In this context, this research expands on previous investigations in this area (Bhatt and Tang 2002; Deininger and Liu 2009; Papias and Ganesan 2009) that discuss the determinants of repayment in microcredit.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section II provides an overview of the related literature on microcredit in general. Section III briefly introduces the SMB and its consulting services. Section IV describes the empirical model and data. Section V presents the estimation results. Section VI presents the conclusions and policy recommendations.

II. Literature Review

There is a large body of literature which examines the various aspects of microcredit, including its poverty reduction effect (Khandker 2005; Nawaz 2010). Among these studies, this paper is related to those which examine the determinants of repayment of microcredit clients. Cull et al. (2007) noted that MFIs are likely to avoid lending to poor clients when they focus primarily on maximizing profits. This implies that it is difficult to attain the two goals of sustainability and outreach simultaneously. Consequently, in microcredit, it becomes very important to understand the determinants of repayment and to establish appropriate incentivizing repayment schemes for disadvantaged clients.

A large theoretical body of work on principal/agent theory shows that joint-liable lending groups strengthen repayment behavior in microcredit (Stiglitz 1990; Besley and Coates 1995), as they facilitate peer monitoring and/or effectively utilize peer selection. Accordingly, the majority of studies on repayment focus on the group lending schemes (Bratton 1986; Zeller 1998; Wydick 1999). However, Sharma and Zeller (1997) find that group lending is particularly effective for low-income households residing in remote areas away from cities. In this respect, most of MFIs in advanced countries and the SMB in Korea do not utilize group lending schemes, where community-based mutual ties are weak.

Several studies have highlighted the effects of other factors on repayment. Field and Pande (2008) find that the repayment period, regardless of whether it is monthly or weekly, does not significant affect repayment. They also show that a monthly repayment schedule would be more cost-efficient. Khandker et al. (1995) find that the operational longevity of the branches in the area increases the default rate. They explain that this feature comes from the possible decrease in the marginal profitability of new projects. Zeller (1998) demonstrates that individual characteristics such as gender, youth, and the size of family do not affect repayment behavior.

Although numerous studies have examined the determinants of repayment, the majority utilize data from developing countries, as microcredit originated and was developed mostly in those countries. As a result, little is known about microcredit in developed countries, although its characteristics could be much different from those in developing countries. With U.S. data, Bhatt and Tang (2002) find that instances of arrears decrease when the bank branch and the client’s business are located in the same area, and when clients are pressured and supervised with regard to their repayments. However, the sample size in Bhatt and Tang (2002) is quite small. The present paper utilizes an extensive administrative dataset from the SMB in Korea, which is the first empirical study of the SMB in Korea. Thus, this study may extend the scope of microcredit research beyond developing countries.

This paper is also related to literature which examines the effects of non-financial business development services. Most microfinance institutions offer business training and consulting services to increase their clients’ self-support capabilities. These non-financial services are considered to be crucial, as they determine the success of microfinance MFIs. Many empirical studies (e.g., Mel et al. 2014; McKernan 2002; Halder 2003) suggest that these services have positive effects on clients’ business performance or income. McKernan (2002) verifies that the increase in the business profits of clients is attributable to Grameen Bank’s training programs, which were designed to teach clients how to use certain types of machinery and to produce products. Halder (2003) discovers that in Bangladesh, women who participated in the BRAC training programs offered there earned higher incomes than those who did not. Mel et al. (2014) compare the effect of training only program with combination of business training and cash grants on female enterprises in Sri Lanka. They find that training only increases the profitability of start-ups, not existing firms. However, if cash grants are combined with a training service, the profits of existing firms also increase.

Unlike the above-mentioned studies, this paper examines the effect of consulting on repayment behavior, rather than on business performance. Several studies also provide empirical results on this theme. Karlan and Valdivia (2011) with a randomized control experiment show that regular business education increases the possibility of on-schedule repayment and client retention. Khandker et al. (1995) also find that membership training has a positive influence on repayment. Godquin (2004) finds positive effects of basic literacy education and health services on repayments in Bangladesh MFIs. Godquin (2004) explains that the provision of non-financial services helps to develop relationships between MFIs and borrowers, which prevents strategic defaults and increases the ability to repay.

Similarly, a pre-lending business consulting service may also have a positive impact on repayment by SMB borrowers due to the strengthened profitability and greater level of closeness with the SMB. However, the frame of the SMB service differs from that of Godquin (2004) in that the service is not regularly provided and is executed by outsourced institutions. Moreover, the characteristics of borrowers in Korea may differ from those in developing countries. Thus, it should be empirically proven whether a pre-lending business consulting service has positive effects on repayment behavior in Korea.

III. The Consulting Service of the Smile Microcredit Bank

The SMB differs in terms of its structure and characteristics from traditional MFIs in developing or developed countries. The government led its creation and expansion, and a number of large corporate banks and private corporate groups are involved in its activities.4 In addition, the SMB arranges business consulting services which are provided by an external outsourced consulting institute. A brief explanation of the consulting program is provided below.

A. Process and Costs

The SMB requires clients whose loans reach a certain amount to enroll in a business consulting program as a condition of receiving a loan. The SMB outsources the consulting services to the Small Enterprise and Market Service (SEMAS),5 a quasi-government organization which operates under the Small and Medium Business Administration (SMBA). A client receives one-on-one consulting for three days, and consultant submits a report to the SMB about the feasibility of the client’s business. However, it is very rare for consultants to report a negative opinion of the feasibility on the business. 6 Thus, the pre-lending consulting service does not function as a screening process.

The consulting program is paid for in part by a government subsidy (90%) and in part by clients (10%). The fee for clients was 50,000 won for the entire program until 2011, becoming 10,000 won per day in 2012. Previously, SEMAS used to assign consultants randomly to SMB clients, but currently clients can choose a consultant directly from the consultant pool.

B. Contents

Because they are one-on-one sessions, the details discussed during the consulting sessions can vary from client to client as well as from consultant to consultant. Each session is divided into two groups based on whether the borrower is already running a business or is starting a new one.

For a client who applies for a loan to cover the facility cost and operating expenses of an existing business, consulting sessions focus on presenting a comprehensive diagnostic review of the business. Consultants attempt to find solutions to current and potential problems so as to ensure the success of the business, including an analysis of the business environment, finances, accounting practices, marketing, store management, and customer management.

On the other hand, consulting programs for clients who start new businesses include a feasibility analysis, a location analysis, an examination of matters related to the opening of the store, business administration, customer management, and other matters of which the client should be aware before launching the business.

C. Rules on Consulting Requirements

As shown in Table 1, the loan threshold at which pre-lending consulting becomes mandatory has varied from time to time. For operating expense loans, since October of 2010, clients whose loan amounts were 10 million won or more have been required to enroll in the consulting program. However, from May to September of 2010, clients with loans worth 5 million won or more were requested to join the program. The changes to the criteria have been random and can therefore be useful if used to examine a possible link between pre-lending consulting and the probability of a business being in arrears.

TABLE 1

CHANGES IN THE CONSULTING REQUIREMENT CRITERIA

Notes: Substitutable indicates that writing up a business plan can be done in lieu of consulting.

For start-up loans, nearly all clients applying for loans had to complete the consulting program regardless of the loan amount. However, between September of 2010 and December of 2011, the consulting requirement applied only to those who borrowed 10 million won or more. Furthermore, start-up business consulting was replaced by the submittal of a business plan during a certain period of time. These inconsistent and random changes can be useful for determining whether the consulting service has a significant impact on preventing or reducing instances of arrears.

D. How a Consulting Service Affects the Repayment Behavior

There are three possible mechanisms by which pre-lending consulting may be correlated with the repayment behavior of clients. First, business consulting can have a positive impact on business performance. As a result, the profits of clients who receive consulting are greater than those of clients who do not. If consulting brings positive changes in the attitudes and the styles of doing business, the client’s profits may increase. With the increased profits, the client would likely display better repayment behavior than clients who did not participate in the consulting program.

Second, pre-lending consulting can build a sense of solidarity which leads to a stronger sense of responsibility concerning repayment. In other words, even if a client’s business performance remains the same, the client may form a sense of attachment to the SMB loan officer during the course of the consulting program, and this attachment may motivate the client to avoid falling behind on repayments. As Godquin (2004) explains, non-financial services may increase the value of the relationship with the MFI and increase the opportunity cost of a strategic default. Although the consulting program is operated by outsourced institutions related the SMB, the consulting program can still build responsibility in clients. Clients may not distinguish the consultant from an SMB employee, and the SMB loan officer may communicate with clients at a deeper level after receiving detailed information from the consultant.

Third, pre-lending consulting may serve as a screening process through which unqualified clients are weeded out. Indeed, it is desirable for this type of screening mechanism to work. Such a filtering process can benefit both existing and new businesses. If an existing business is not profitable and is uncompetitive, closing it down rather than incurring additional loans could be a better choice for the owner. In contrast, if the chance of failure is high for a client who plans to start a new business, it is better to let the client take the time to ensure that everything is ready instead of hurrying and prematurely opening the business. In these situations, the consulting program can help clients make better choices by giving them sufficient time to stop and reconsider their options. However, if such a screening mechanism does exist, this means that there is a selection rule that may have affected the sample.

However, as mentioned earlier, it is very rare for SEMAS consultants to report that clients are ineligible for a loan, and such a screening mechanism is practically non-existent in our sample. Therefore, this research will focus on the first two possible mechanisms: how consulting can improve the client’s business performance and how it may build a sense of solidarity.

IV. Empirical Specification and Data

A. Empirical Specification

The previous section discussed the characteristics of business consulting with regard to loans from the SMB. In the following basic model, we use logistic regression to estimate the effect of consulting on the probability of repayment behavior:

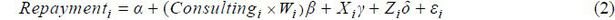

Here, the dependent variable Repaymenti is a dummy variable which has a value of one when borrower i has made regular repayments on time (no arrears), taking a value of zero otherwise. Consultingi is the key regressor of interest, indicating that the borrower was required to enroll in one-on-one consulting, which is determined by the loan origination timing and the amount of the loan. If one-on-one business consulting has a positive effect on repayment behavior, the coefficient Consultingi would have a positive value.

Xi is a matrix of control variables. It includes the characteristics of the loans, in this case the amount of the loan and the length of the grace period. During a certain period, the requirement of mandatory consulting for start-up loan applicants could be satisfied instead by the writing of a business plan. Thus, a variable for this type of substitution is also included in the model for start-up loans.

Xi also includes individual characteristics of borrower i, in this case the credit score, a dummy variable for male, and the age of the borrower. Credit scores in Korea have a value between one and ten, where the credit score increases when the credit rating worsens. Therefore, a value of ten represents the worst credit rating, and the coefficient of the credit rating is expected to be negative. Sometimes, borrowers do not have a credit rating due to the lack of enough credit history. In this case, we assign a value of eleven, which is inferior to other borrowers with credit ratings, and we add a dummy variable to signify no credit rating. Xi also includes variables pertaining to financial status, such as the log of the average monthly income, the log of the existing total debt at the point of loan application, and the log of the total value of all assets of the borrower.

Additionally, different loan origination times should be controlled, as there would be a tendency of more instances of arrears for older loans with a larger number of payments due. Therefore, a set of control variables, denoted as Zi, includes the remaining months to maturity and the number of expected payments due. As the effect of different loan origination times could be non-linear, the number of expected payments due is included both as a continuous variable and as several discrete dummy variables.

Moreover, the effects of consulting on repayment may not be the same for all borrowers. For example, the effect of consulting could be greater with borrowers who have more business experience. Thus, we extend the basic regression model with the interaction term Consultingi × Wi to capture the effects of consulting on repayment according to the various types of borrowers.

We formulate several variations of Wi, which is a set of categorical variables. These are gender groups, age groups, and the types of regions based on the business site. For the region, we divide them into three groups: big cities, small cities, and rural areas. Big cities include Seoul and six large metropolitan cities. Rural areas are identified with the administrative township “Eup” or “Myeon,” indicating a countryside area.

B. Data

The data for the analysis consists of confidential administrative data from the SMB. The raw data consists of all loans originated from January of 2010, when the SMB started to offer microcredit through its branches; 7 it includes client information from loan application documents, such as the gender and credit ratings of the borrowers and the details of their loans. Information about repayment behavior is constructed by comparing the number of actual payments and that of expected payments that must be made until the time of the observation,8 December of 2012.

Mandatory consulting is only required for clients using standardized products that are commonly offered in all branches; thus, several special products which are offered certain specialized branches are excluded. Among the standardized products,9 the two most common products are analyzed in this paper, i.e., start-up loans for rent deposits by new businesses and business operating loans for existing businesses.

To construct the sample for the regression, we use loans which were approved from April of 2010 to January of 2012 in order to exclude loans provided immediately after the SMB was launched. This subset is suitable for the analysis because the criteria for the consulting requirement changed for both business operating loans and start-up loans during this period. As a robustness check, we also conducted the same regression with loans that were originated in different periods.

We also exclude loans that are either too small or too large, as the cut-off point for mandatory consulting was established based on the loan amount. In the panel of start-up loans for new businesses, we use the subset of loans between 7 million and 16 million won, as the cut-off point was 10 million won in a certain period. On the other hand, for business operating loans, we use the subset of loans between 3 million and 12 million won, as the cut-off point was 5 million or 10 million won. Robustness tests are also performed by modifying the range of the loan amount.

Outliers are removed from the sample, such as loans to the clients who had more than 8 million won in monthly income, more than 350 million won in assets, or more than 300 million won in debt. Some clients were allowed to roll over their existing loan by taking out a new loan10, and some clients took out loans multiple times. Both such cases are also eliminated.

Summary statistics of the variables used in the empirical analysis are shown in Table 2.

V. Results and Discussion

A. Business Operating Loans for Existing Businesses

In this section, we present and interpret the results of the estimation of the impact of participation in pre-lending business consulting on repayment performance. The results of the main regression with business operating loans are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3

MAIN REGRESSION RESULTS: OPERATING LOANS

Notes: Robust standard errors are in parentheses; the dependent variable is repayment. Region-fixed effects are included in all specifications.

*** significant at the 1 percent level.

** significant at the 5 percent level.

* significant at the 10 percent level.

Table 3 displays the regression results of four specifications. The first two columns provide the marginal effect and the estimates of the base model. In specification (2), we control for the debt-to-income ratio and the debt-to-assets ratio instead of the log of assets, the log of monthly income and the log of debt. In specification (3), we control for possible non-linear effects with regard to the number of expected payments with several dummy variables instead of a continuous variable. In specification (4) we use dummy variables for the age groups instead of a continuous age variable to control for a possible non-linear effect of age. All results reported are estimated with the logistic regression model.

The results for all specifications show a positive and significant effect of pre-lending business consulting on the repayment behavior of existing entrepreneurs who took out operating loans. According to the marginal effect in the first column, for the average borrower, the probability of repayment without arrears increases by 5% when the borrower enrolls in the consulting service. Thus, enrolling in one-on-one business consulting has an impact similar to an increase of one grade of the credit score on the repayment performance of a typical existing entrepreneur.

This result implies that non-financial services in Korea may enhance the financial performance levels of MFIs through improved repayment behavior, as in developing countries. As the repayment behavior of micro-entrepreneurs is strongly related to the cash flow of the business, it is highly likely that the regression result is caused by the positive impact of the business consulting on the profits of micro-entrepreneurs. If an existing entrepreneur could gain useful ideas or advice from an expert from an objective perspective, the business performance of the borrower will likely improve. Utilizing the microcredit data of developing countries, Mel et al. (2014), Halder (2003), and McKernan (2002) also find that non-financial services have a positive impact on the profits of borrowers. However, to clarify this mechanism more directly, an additional analysis with business performance data should be conducted, though this is not available at this point.

On the other hand, the positive impact of one-on-one business consulting can also be explained by the strengthened responsibility of borrowers after in-depth communication prior to receiving a loan. Karlan and Valdivia (2011) find that regular entrepreneurship training has a positive impact on repayment performance and client retention, whereas such a service has little impact on key business outcomes such as revenue or profit levels. Godquin (2004) also finds a positive impact of non-financial services on repayment performance which is not directly related to the performance of the business, such as basic literacy education and access to health services. In the SMB, although consulting is neither regularly nor directly executed by the staff, the experience of sincere communication prior to lending may have strengthened the loyalty of borrowers to the SMB.

In both cases, it is certain that business consulting has a positive impact on the financial stability of the SMB through improved repayment performance. Currently, the recipients of pre-lending consulting for business operating loan are very limited. The consulting requirement applies only to basic products, and loans of less than 10 million won are excluded, even in basic products. Therefore, the SMB must expand its one-on-one consulting service to cover more existing micro-entrepreneurs. This will support the business performance of clients and the repayment management efforts of the SMB.

The coefficients of other variables in Table 3 are reasonable. Credit rating has a negative and significant impact on repayment performance, as a higher credit score signifies an inferior credit rating in Korea. The length of the grace period has a negative and significant coefficient, implying that originating loans without a grace period is a better management strategy for repayment by existing entrepreneurs. Income and existing debt have an insignificant impact, as these factors are already controlled through the credit rating variables.

Table 4 presents the results of the robustness checks, including estimates with pseudo-consulting indicators and estimates with a different subset. Generally, borrowers with the better credit ratings are eligible for larger loan amounts. This can also be applied to the SMB, although the SMB focuses more on borrowers’ needs as compared to other typical financial institutions. Thus, we control the size of the loan and the credit rating, and we utilize the period when the cut-off point was randomly changed. However, there remains the possibility that the positive impact of consulting on repayment is a spurious relationship stemming from the fact that borrowers with larger loans tend to be more able to repay them.

TABLE 4

ROBUSTNESS CHECKS: OPERATING LOANS

Notes: Robust standard errors are in parentheses, estimates from the logit regression are represented, and the dependent variable is repayment. Region-fixed effects are included in all specifications.

*** significant at the 1 percent level.

** significant at the 5 percent level.

* significant at the 10 percent level.

To check the robustness further, we create several pseudo-consulting variables. In specification (1) of Table 4, the pseudo-consulting variable represents loans that are greater than 8 million won, and the estimate is insignificant. In specification (2), we use a different pseudo-consulting variable which counterfactually differentiates the period when the cut-off point was changed; this coefficient is also insignificant. Thus, a simple division into large and small amounts cannot determine the source of the impact of consulting on repayment.

In addition, although consulting was mandatory according to the SMB regardless of the willingness of the borrower, it is necessary to account for the possibility that borrowers intentionally evade consulting by taking out loans which fall just under the threshold. In specification (3), we construct a new subset in which observations of loan amounts which are slightly under this threshold, when the initial desired amount of the borrower exceeded it, are removed.11 Even with this subset, main findings do not change.

We also conduct additional robustness tests. In specification (4), we shorten the loan origination period to February of 2011. In specification (5), we change the range of the loan amount of samples, making it between 4 million and 15 million won. In specification (6), we use repayment information as observed six month later, in June of 2013 instead of December of 2012. The results are still positive and significant for all specifications, as in the main regression.12

B. The Effect of Consulting according to the Types of Borrowers of Business Operating Loans

The above-mentioned positive impact of consulting on repayment performance among existing micro-entrepreneurs can vary according to the type of borrower. Thus, we conduct a regression of Equation (2), taking into account interaction terms of consulting variables and each type of borrower. These include gender, age group, and region. Table 5 presents the estimates of the interaction terms.

TABLE 5

INTERACTION TERMS: OPERATING LOANS

Notes: Robust standard errors are in parentheses; estimates from the logit regression are represented. The dependent variable is repayment. In all specifications, loan amount, grace period, credit rating, no credit score, gender, age, No. of expected payment, months to the maturity, and constant are included; In specification (1), (3), and (5), log of monthly income, log of assets, log of debt and region fixed effects are added.

*** significant at the 1 percent level.

** significant at the 5 percent level.

* significant at the 10 percent level.

The first and second columns show that the effect of consulting on repayment performance is greater for male borrowers than for female borrowers. We may interpret this result in light of two possible situations. Firstly, as most consultants are males at the institutions providing the consultations,13 female borrowers may not form a sense of solidarity with male consultants in the manner that male borrowers do. Secondly, in Korea, it is common for small businesses to be run by entire families. Thus, a female borrower may have a husband who practically manages the business. In this case, an effective change will not come about after only the female borrower enrolls in the business consulting. Therefore, to provide more effective business consulting, it is suggested to let the all of the business partners to undertake consulting together.

The third and fourth columns indicate that the estimated coefficients of the interaction terms are significant and positive only for borrowers in their 40s and 50s. This result suggests that business consulting is effective for experienced borrowers in their 40s and 50s. As most people hold college degrees in Korea, borrowers under 30 may not have enough experience. On the other hand, borrowers in their 60s have had sufficient time, especially if they start their businesses soon after retirement, which is very common in Korea. Therefore, to promote the effectiveness of consulting on inexperienced borrowers, it is necessary to supplement their insufficient business experience with business training and education as well as one-on-one consulting. Clients who lack experience may find a training program tailored to meet their needs extremely helpful when offered in conjunction with a consulting program.

The fifth and sixth columns show the estimated interaction terms of the consulting indicator and the regions of the business sites. These results show a significant and positive effect only for large cities such as Seoul and the six metropolitan cities. This result may show that the quality of the consultants and the content of the consultations in small cities and in remote rural areas are not as good as they are in large cities. Hence, it is necessary to strengthen the quality of consulting in areas other than large cities.

C. Start-up Loans for New Business

The results of the main regression for the group of start-up loans are shown in Table 6. In all specification, borrowers with no credit rating are eliminated in the sample as all of them made full repayment. We present five different specifications, including the base model in the first column. In specification (2), we control for the debt-to-income ratio and the debt-to-assets ratio. In specification (3), we use several dummy variables for the number of expected payments instead of a continuous variable. In specification (4) we use dummy variables for the age groups instead of a continuous age variable. In specification (5), we include the index of substitution, i.e., writing up a business plan instead of enrolling in consulting. In all five specifications, the consulting variable in start-up loans shows a statistically insignificant coefficient, indicating that repayments by new start-ups do not improve with one-on-one pre-lending consultations.

TABLE 6

MAIN REGRESSION RESULTS: START-UP LOANS

Notes: Robust standard errors are in parentheses, and the dependent variable is repayment. Estimates from the logit regression are represented. The borrowers with no credit rating are eliminated in the sample as all of them made full repayment.

*** significant at the 1 percent level.

** significant at the 5 percent level.

* significant at the 10 percent level.

One reason for the insignificance effect of pre-lending consulting could be incomprehension by inexperienced start-ups. Experienced borrowers who receive operating loans for existing firms tend to repay better if they enroll in pre-lending consulting, as in the above results. In contrast, inexperienced borrowers who start new businesses may not be affected by this type of consulting, as they do not fully understand what the consultants suggest. Mel et al. (2014), studying female enterprises in Sri Lanka, find that business training for female enterprises can effectively increase profits, even for new owners. The business training in Mel et al. (2014) was very intensive compared to the three-day consulting service of the SMB. The business training service consists of a three-day course on developing business ideas, a five-day course on starting a business,14 and one day of technical training which varies according to the type of business. Thus, to complement the consulting service for inexperienced start-ups, business training or education sessions may be beneficial.

Moreover, the SMB provides a one-shot service in the initial stage, while the non-financial service in Karlan and Valdivia (2011) continued regularly for one or two years. Regular service is not only more advantageous to establish responsibility in clients but also effective at enhancing business performance. As borrowers of start-up loans do not have enough experience or knowledge about their business, they may not sufficiently understand what the consultant suggests or explains. The borrower may also have difficulty when encountering unexpected situations despite any confidence during the initial steps. Thus, to make the business consulting for effective for start-ups, regular check-ups may be required rather than a one-shot pre-lending service.

In all specifications, most variables did not show a significant coefficient, except for credit rating and gender. The coefficient of credit rating is significant and negative, as expected, showing that repayment behavior is degraded as the credit rating becomes poorer (i.e., as the credit score increases). The dummy for male borrower shows a significant and negative coefficient, and this is consistent to earlier findings in the literature which show that female borrowers have display repayment behavior (Kevane and Wydick 2001, Khandker et al. 1995; Pitt and Khandker 1998; Sharma and Zeller 1997).

Table 7 shows the results of the robustness test. The first concern was selection error, e.g., when borrowers intentionally avoid consulting by taking out a smaller loan when they originally wanted a larger loan. Thus we remove observations of borrowers if the loan amount is smaller than the cut-off amount when their initial desired loan amount was larger.15 In specification (1), we exclude these observations from the sample. Even after removing these observations, the coefficient of the consulting variable remains insignificant.

TABLE 7

ROBUSTNESS CHECKS: START-UP LOANS

Notes: Robust standard errors are in parentheses, estimates from the logit regression are represented, and the dependent variable is repayment. Region fixed effects are included in all specifications. The borrowers with no credit rating are eliminated except the specification (2).

*** significant at the 1 percent level.

** significant at the 5 percent level.

* significant at the 10 percent level.

We also conducted additional robustness tests. In specification (2), we include the borrowers with no credit rating in the sample. In specification (3), we shorten the loan origination period. In specification (4), we change the range of the loan amount of the samples to between 6 and 13 million won. In specification (5), we use the repayment information observed six month later, in June of 2013. The results in these cases are similar to those of the main regression, and the coefficient of consulting remains insignificant in all cases.

VI. Concluding Remarks

This research attempts to determine the effects of pre-lending business consulting on the probability of repayment by analyzing confidential data from the Smile Microcredit Bank in Korea. The SMB has randomly changed the criteria which determine which clients are required to enroll in a three-day one-on-one consulting program. This study utilized this as an identification strategy.

The pre-lending consulting service made a significant difference among clients who were already running a business. Clients who participated in the consulting program had a far lower rate of having their payments go into arrears than those who did not. Given the significant difference in repayment behavior, more clients in receipt of operating loans should undergo this type of consulting program instead of limiting eligibility to clients who borrow 10 million won or more. In addition, financially disadvantaged business owners using other microcredit products should also be encouraged to take the SEMAS consulting program.

In contrast, in the sample of clients who received start-up business loans, no significant differences in behaviors are observed between clients who experienced the pre-lending consulting program and those who did not. Thus, other types of support in addition to the consulting program may be necessary for those starting businesses, as they must carry out extensive preparatory work prior to opening the business. For example, clients should be required to complete an educational program so that they may better understand the details discussed in the consulting sessions. Moreover, post-lending consulting should be provided on a regular basis to give clients timely advice and help them tackle unexpected problems that may arise during the course of running their business.

This research is meaningful in that empirical study of microcredit is scarce in countries other than developing countries. However, more research needs to be done in the future in an effort to determine the direct effect of consulting programs on business performance from a long-term perspective. Furthermore, a randomized control treatment should be conducted so as to increase the validity of the findings in this research.

This research looks only at pre-lending consulting outsourced to an external agency, but it would be interesting and necessary to determine how mentoring or consulting directly provided by loan officers and how a group-training program rather than a one-on-one program can change clients’ behavior and reduce situations of arrears. Such efforts are left for future work.

Notes

This paper developed chapter 6 of Oh, “Microcredit Products for Low-Income and Low-Credit People in Korea: Focusing on Political Products Driven by Financial Inclusion Policy,” Policy Research Series 2013-08, Korea Development Institute, 2013.

Political microcredit products include the New Hope Loans of commercial banks and the Sunshine Loans of non-bank depository institutions.

Potential welfare recipients, welfare recipients, and people eligible for the earned income tax credit (EITC).

Five banks (KB, IBK, Shinhan, Woori, and Hana) and six corporate groups (LG, SK, Lotte, Samsung, Posco, Hyundai Motor ) operate SMB branches within their donation fund.

SEMAS fosters small enterprises, traditional markets providing education, consulting, and marketing support.

There was only one case up until 2013 for which the consultant assessed the client’s business as not feasible. SEMAS consultants may have an incentive not to be harsh on SMB clients, as they are also evaluated by these clients, and their remuneration depends on the average evaluation scores.

The data only contains the clients of the SMB branches, excluding on-lending clients of the traditional market and other microcredit institutions.

The raw data does not include information about how long the loan is overdue or when arrears occurred.

Standardized products include loans for franchises, loans for education, and loans for facilities, but business operating loans and start-up loans are most common.

Roll-over loans are occasionally made to manage repayments, refreshing loans in arrears for a longer period. However, these loans are excluded, as information about the older loans is not available.

When the cut-off amount is 10 million won, we exclude borrowers who take out loans which are between 9.6 million and 10 million won when the originally desired amount was more than 10 million won on the loan application document. Similarly, with the cut-off amount of 5 million won, loans of between 4.6 million and 5 million won are excluded when the initial desired amount was more than 5 million won.

For additional robustness checks, we used several dummy variables for credit ratings instead of a continuous variable to control for a non-linear effect. We also included an interaction term for consulting and the period when cut-off point was changed to control for a possible mean effect of the period itself. The regression results were still consistent.

In 2014, the number of male consultants was 1,012 while the number of female consultants was 206.

References

, & (2001). Delivering Microfinance in Developing Countries: Controversies and Policy Perspective. Policy Studies Journal, 29(2), 319-333, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2001.tb02095.x.

, & (1995). Group Lending, Repayment Incentives and Social Collateral. Journal of Development Economics, 46, 1-18, https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(94)00045-E.

(1986). Financing Smallholder Production: A Comparison of Individual and Group Credit Schemes in Zimbabwe. Public Administration and Development, 6, 115-132, https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.4230060202.

, , & (2007). Financial Performance and Outreach: A Global Analysis of Leading Microbanks. The Economic Journal, 117(517), F107-F133, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02017.x.

. (2004). Microfinance Repayment Performance in Bangladesh: How to Improve the Allocation of Loans by MFIs. World Development, 32(11), 1909-1926, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.05.011.

(2003). BRAC’s Business Development Services—Do They Pay? Small Enterprise Development, 14(2), 26-35, https://doi.org/10.3362/0957-1329.2003.019.

, & (2011). Teaching Entrepreneurship: Impact of Business Training on Microfinance Clients and Institutions. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(2), 510-527, https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00074.

, & (2001). Microenterprise Lending to Female Entrepreneurs: Sacrificing Economic Growth for Poverty Alleviation? World Development, 29(7), 1225-1236, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00032-8.

(2005). Microfinance and Poverty: Evidence Using Panel Data from Bangladesh. The World Bank Economic Review, 19(2), 263-286, https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhi008.

(2002). The Impact of Microcredit Programs on Self- employment Profits: Do Noncredit Program Aspects Matter? Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(1), 93-115, https://doi.org/10.1162/003465302317331946.

, , & (2014). Business Training and Female Enterprise Start-up, Growth, and Dynamics: Experimental Evidence from Sri Lanka. Journal of Development Economics, 106, 199-210, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.09.005.

(2010). Microfinance and Poverty Reduction: Evidence from a Village Study in Bangladesh. Journal of Asian and African studies, 45(6), 670-683, https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909610383812.

, & (2009). Repayment Behaviour in Credit and Savings Cooperative Societies: Empirical and Theoretical Evidence from Rural Rwanda. International Journal of Social Economics, 36(5), 608-625, https://doi.org/10.1108/03068290910954059.

, & (1997). Repayment Performance in Group-based Credit Programs in Bangladesh. World development, 25(10), 1731-1742, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00063-6.

(1998). Determinant of Repayment Performance in Credit Groups: The Role of Program Design, Intragroup Risk Pooling, and Social Cohesion. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 46(3), 599-621, https://doi.org/10.1086/452360.